network literacy

Practices, Definitions, ImplicationsDavid Sifry reported in April 2007 that there are more than 70 million blogs on the web, with 120,000 more created each day; their popularity should prompt us to rethink what it means to be literate in networked writing environments. This project examines a cross-section of one blogging community--mom bloggers--as a beginning attempt.

introduction

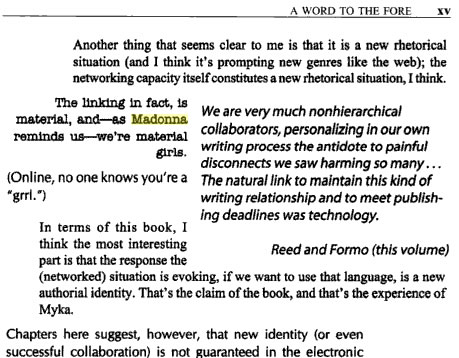

In the foreword of Electronic Collaboration in the Humanities, Myka Vielstimmig (2004) broke generic print conventions in both visual format and style. The paragraphs resisted linearity, with word chunks and quotations nested within one another and juxtaposed in columns. Each rectangle of text appeared to exist on its own, with a specific tone—some playful, some serious, some quoting from the essays in the book, some in which Vielstimmig referred to herself in the third person—and at the same time each rectangle worked in conversation with the other rectangles surrounding it. For instance, the following portion of the foreword included a number of fonts, pop culture and scholarly references, and a range of voices to broach the rhetorical situation that writers construct in networked environments:

The effect on the reader is jarring, both visually and rhetorically, if one is accustomed to allowing the top-to-bottom, left-to-right conventions of print guide her eye. Vielstimmig speculated that “the networking capacity itself constitutes a new rhetorical situation,” and then presented both her semi-tangential reference to Madonna and the quote from Reed and Forno, who explained that technology has afforded them a solution to some of the problems of formal collaboration. Vielstimmig followed her Madonna tangent one step more, connecting Reed and Forno's non-hierarchical use of technology to the observation “Online, no one knows you're a ‘grrl.’” At the end of this exchange with herself, Vielstimmig was able to fit the pieces of her preliminary reaction to the essays collected in Electronic Collaboration into a larger claim: “the response the (networked) situation is evoking…is a new authorial identity.”

Vielstimmig's approach to writing the foreword is classic form-follows-function. From her creative use of font, layout, and voice, readers get the distinct impression of being “in on” the conversation that took place in the construction of the foreword. Readers have a keen sense of Vielstimmig’s process; there is a distinct personal quality to the text that emerges from her public wrangling with both her own and others’ ideas. The recursive style mirrors collaboration, and the product doesn’t have a distinct authorial identity, which is often one symptom (or an advantage) of working in a networked writing environment.

The kind of social writing practices that Vielstimmig gestured toward are better suited to electronic spaces. These social writing practices have been described as “network literacy” by Jill Walker, author of the weblog jill/txt and professor in the Department of Humanistic Informatics at the University of Bergen. In 2003, she defined network literacy as “writing in a distributed, collaborative environment” (Walker), and she has since argued that writing is now more than ever undeniably social. But what does writing in a distributed, collaborative environment look like? Vielstimmig’s foreword might give us an idea--recursive, simultaneously personal and public, requiring substantial audience engagement--but the print medium prevents it from being truly collaborative and networked. The print medium is still able to veil the social nature of Vielstimmig’s process: the end product is billed as single-authored. So how does the immediate social nature of applications such as blogs and wikis inform and change our conventional notions of readers’ and writers’ roles—especially in the ways such applications are multiply-authored by the audience itself? To answer such questions, existing theories of new media literacy(ies), as well as network theory, provide a framework through which we can examine and describe networked writing practices.