Queerness, sexuality, technology, and writing: How do queers write ourselves when we write in cyberspace?

Jonathan Alexander, Barclay Barrios, Samantha Blackmon, Angela Crow, Keith Dorwick, Jacqueline Rhodes, and Randal Woodland

University of Cincinnati, Rutgers, Purdue University, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, California State University–San Bernadino, University of Michigan–Dearborn

“Queerness, Sexuality, Technology, and Writing: How Do Queers Write Ourselves When We Write in Cyberspace?” is primarily an edited conversation transcript on how queer writing is changed by and influences cyberspace use by queers. The conversation took place on January 21, 2004. Participants Jonathan Alexander, Barclay Barrios, Samantha Blackmon, Angela Crow, Keith Dorwick, Jacqueline Rhodes and Randal Woodland gathered in AcadianaMOO (http://acadiana.arthmoor.com/cuppa) and annotated the conversations in the weeks that followed.

Keywords: Gender, LGBT/queer, MOO, Online writing, Race, Sexuality, Subaltern, Technology, Virtual reality, Wit.

1. Introduction

This piece is an example of a successful collaboration on several levels. Its genesis was a series of conversations between Jonathon Alexander, Angela Crow and Keith Dorwick. As we talked through plans for an article intended for this special issue of Computers and Composition on “Sexualities, Technologies, and the Teaching of Writing,” and struggled with the relation between the resources we frequent online and our queer identities, we started wondering if we could imagine being queer without the Internet. While talking about the types of queer sites we frequent, and whether we could live our own queer lives without technology, one of us asked, only half in jest, “where would I be without the gay.com Phone Fun room?” In attempting to say something about queerness, sexuality, technology and writing, however, we realized that we had many questions that required more than our perspectives and found ourselves wondering about several issues.

We, therefore, asked a number of other queer-writing theorists to participate in a virtual conversation that would speak to the impact of cybertechnologies, such as the Web, on our sense of queer life and writing (this introduction is based on that invitation), and are grateful to Barclay Barrios, Samantha Blackmon, Jacqueline Rhodes and Randal Woodland for joining the conversation. The group of seven scholars who gathered that night reflected a wide range of positions and locations. We are different ages, classes, ethnicities, races, genders, and members of various subcommunities within a decidedly nonmonolithic, wider queer community. The conversation is richer for its diversity.

Like many scholarly conversations, there are several layers of discourse here: First, participants had several questions in hand (developed by Jonathan, Angela and Keith) several weeks before the conversation took place—providing all seven participants the opportunity to think through how writing and queerness intersect, for us at least, on the Internet. We began by asking what our favorite queer site is or which queer site we see as most significant (and why). And we asked these additional questions:

The conversation took place in AcadianaMOO (a synchronous multi-user chat domain) of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette <http://acadiana.arthmoor.com/cuppa> for Java-compliant browsers or <acadiana.arthmoor.com, port 7777> for MOO/MUD clients; Keith then edited and arranged the transcript to better serve readers. Largely, the editing attempted to reflect the several ongoing threads that existed by eliminating the discontinuities in the conversation that resulted from such factors as differences in keyboarding speed, lag time, and bad connections. Finally, after-the-fact annotations from participants were added to the edited version, allowing them a chance to revisit and rethink the conversation asynchronously. We intend the edited transcript and its annotations to serve as an article and a record of a hybrid synchronous and asynchronous event, with all seven participants sharing equal co-authorship.

The authors would like to note that MOO language is its own particular, unique, and wonderful discourse; the editing of the transcript did not try to fix or change those qualities by correcting what would be grammatical and spelling errors in a more traditional text. However, reordering the conversation involved difficult editorial decisions and relied on the (perhaps faulty) memory of the editor. Therefore, following Dene Grigar’s suggestion for an earlier MOO-based article for Computers and Composition, the original conversation, without editorial changes, is archived for scholarly purposes at <http://www.ucs.louisiana.edu/~kxd4350/queer>.

2. Conversation

Keith [Dorwick, University of Louisiana at Lafayette] says, “welcome to AcadianaMOO, and thanks all for coming... the recorder is running and we’re live from Acadiana! O.K., first question: We will begin by asking what your favorite queer site is or which queer site you see as most significant (and why), and I guess as one of the authors of that question, I could see it meaning either personally or professionally, or both.”

Barclay [Barrios, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey–New Brunswick] says, “umm are we going in order, or jumping in?”

Jonathan [Alexander, University of Cincinnati] says, “Jump in, Barclay.”

Saffista [Samantha Blackmon, Purdue University] says, “Interestingly enough my favorite/most signif site isn’t exclusively queer, does it still count?”

Barclay says, “My favorite site? Hrm. The problem I have with this question is that to answer is to out my specific desires, something I’d rather not do until I’m tenured. But with this hesitation, I guess I am at least willing to admit that my favorite queer sites have a lot to do with meeting people who share my particular configurations of queer desires. I’m hoping that will be answer enough. As for the most significant queer site, I would actually have to choose something that’s neither specifically queer nor actually a site: America Online [AOL]: it allows for multiple, stable online identities (allowing people to explore new queer identities and manage their outness online); it has chat rooms for all kinds of queers (allowing queers to find other queers); its instant messaging creates private conversation in public online spaces (allowing more private explorations of desires and interests); and it’s where I first started learning HTML [hypertext markup language]. Plus, there was the GLBT [gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender] area & what was it called? On Q?”

Jonathan says, “I’m experiencing a little of what Barclay mentions about hesitating to name one’s desire—even on the other side of the tenure line...”

Barclay nods

Saffista says, “It still counts, in my opinion...”

Keith adds, yes, it counts in my opinion, too; in fact, most queer spaces on the Internet are embedded in other, mostly commercial, mostly straight spaces. I’m thinking here of Yahoo.com, which has wildly popular M4M rooms, and AOL, which also offers queer spaces within chat spaces that are mostly nonqueer. The M4M rooms were first created on AOL (and later on Yahoo). They exist primarily for use by MSMs [men who have sex with men] to meet. These spaces are not identified as gay or bisexual, and many of the men (and sometimes boys) who use them would not identify as such. They are largely used to meet other individuals for sex without the supposed stigma of being called gay. Meanwhile, all-gay spaces such as Gay.com <http://www.gay.com> are interesting because while largely or entirely gay, other locations (to borrow a term from sociology) can become markers of great difference; I’m thinking here of people who happen to be HIV-positive or people of color, or, for that matter, women, can find themselves embedded in an architecture or hierarchy in which White, gay, male, HIV- [those not infected with Human-Immunodeficiency Syndrome Virus] sexuality is the norm. This means you have to go and search out the spaces in which others like yourself can be found if you’re not entirely part of the mainstream as gay.com sees mainstream sexuality: gay but otherwise part of the hegemonic structure that too well defines our culture to date.

RandyW [Randall Woodlawn, University of Michigan–Dearborn] says, “I was going to say AOL as well—in part to watch the smoke come out of Keith’s ears.”

Keith grimaces; he’s had a long history of having to deal with AOL customers who also happened to be students in his classes. He says, “I’ve had to troubleshoot why some students couldn’t get onto Microsoft’s IRC servers—before they pulled the plug on IRC—only to find they had one thing in common: They were using AOL to connect, and Microsoft had banned AOL. The one character I banned temporarily from my MOO was an AOL customer. I could go on but suffice it to say that AOL customers benefit from the ease with which AOL’s software makes connectivity possible, but this also means they can be a bit inexperienced and get themselves in social difficulties as they blunder through cyberspace. Hence, Randy’s remark, who has listened to me grumble about this for many years now.”

Saffista says, “Ok, then I have to vote for Blackplanet.com <www.blackplanet.com> or at least the queer spaces there. It seems that this is where every Black queer person that I run across hangs out online. Blackplanet fills a big void for most Q [queer] Black folk out in the sticks where there are few Black folk or out Q folk.”

Saffista adds, but even more than this, I wonder if this is because many queer online spaces still seem to be primarily inhabited by Caucasians. I think that in many cases the need to be among people of color carries over into online spaces and become even more important than being with other queer folks. The major difference here may be that the GLBT component of one’s identity can be primary for Caucasians because there is no need for racial identification; they are the default. The same is true on Blackplanet.com, African American is the default and from there we can begin to explore other components. In One More River to Cross: Black & Gay in America, Keith Boykin (1996) hit the nail on the head when he wrote:

When given the choice between our Black identity and our gay identity, many Blacks who are openly lesbian or gay still find more comfort among straight Blacks than among White lesbians and gay (sic). Partly because African Americans tend to be more disadvantaged than Whites, we often prefer to deal with straight, nonhomophobic Blacks than with White lesbians and gays, many of whom have trouble understanding this concept. For White lesbians and gays, sexual orientation identification is usually more important than their racial identification. They tend to see the world through the lens of their lesbian and gay eyes, while Black lesbians and gays see it through a prism of colors (p. 88).

Jonathan says, “But I will say that my favorite ‘queer sites’—whatever THAT means—are ones that have initially pushed my boundaries of sexuality, ones that have provoked me to reconsider what I, personally, find attractive, or am attracted to.”

Barclay says, “What’s interesting, then, Jonathan, is that the Web lets us be out online in ways that we may not be comfortable in everyone knowing.”

Jonathan says, “Indeed, Barclay.”

Jonathan adds, that Michael Warner (1999) told us in The Trouble with Normal

that “sexual autonomy requires more than freedom of choice, tolerance, and the liberalization of sex laws. It requires access to pleasures and possibilities, since people commonly do not know their desires until they find them”. That’s what the Internet provides for me—“access to pleasures and possibilities” and a way to encounter desires I did not know I had (or perhaps didn’t have until I found them) (p. 7).

Barclay says, “Saffista, would you say then that the intersection of race and sexuality creates particular complications?”

Saffista says, “Definitely. Coming out as African American and queer in a predominately White space brings up all kinds of issues that don’t usually get brought up when you come out in a Black queer space or in a space where physical racial markers are not visible, if you feel comfortable passing either actively by speaking the text or inactively by allowing people to assume that you are the default.”

Saffista adds, when African American homosexuals are out as Black, either visually or textually, their “sexual orientation can often be just another example of their otherness, making them less inclined to view this aspect of their identity as central to who they are. Black lesbians add another layer of difference from the cultural standard by virtue of their gender” (Boykin, p. 90, 1996). I think that this is especially true in the case of women who can be classified by “scare quotes” butch, trade, or bulldaggers because the physical manifestation of their sexual orientation is more obvious in nonAfrican American, nonurban environments. In urban areas it can be difficult to distinguish dykes from trendy girls and I say that only half jokingly.

Keith says, “For me the site of choice is certainly gay.com though it drives me crazy in a lot of ways... it’s SUCH a commercial site, and it’s been a lifesaver. I grew up in Chicago, and worked there for many years... and then moved to a relatively small university town in Louisiana and felt VERY isolated, so without it, I don’t know how I would have survived a distance relationship and all that good stuff.”

Jackie [Jacqueline Rhodes, California State University–San Bernardino] says, “I’ve been trying to figure out what might be the MOST significant queer site for me....”

Barclay says, “gay.com is a biggie, yes—but for many of the same reasons I would say AOL is.”

Jackie says, “As I was thinking about it, though, I realized that a lot of my queer space/experience online has been centered in spaces like this one.”

Jackie pokes Jonathan

Barclay says, “like IRC, too, Jackie?”

Barclay has a history with IRC, too.

Jackie says, “Barclay, yes, IRC and MOOs—interactive spaces with pick-your-own identity.”

Saffista says [to Jackie], “or developing your own identity. For me, these spaces were more of a place of development. A place to explore the nuances of my identity among a group of people who only knew the online, queer me and not the offline, struggling me. Being online gave me a place to move through the offline world where my mother still tried to persuade me to ‘at least put on a little lipstick’ every time we went someplace together.”

RandyW says, “I think the significance of AOL was (and perhaps no longer is) a) the ways it made all parts of the Internet (including the queer parts) available to almost anyone (without special tools and/or costumes), and b) the way in which LGBT folk ‘queered’ AOL and its standard array of communicative avenues.”

Barclay says, “Though costumes can come in handy, Randy.”

Barclay smiles

Barclay adds that, in his experience, some of the differences between AOL, IRC, and gay.com all have to do with the issues of identity-formation identified by Jackie. It seems as though sites that require a financial investment, like AOL, inherently promote the creation of a stable identity. After all, when you’re paying for a service, you want to remain who you choose to be. Gay.com, in contrast has a free basic chat service and people seem to come and go there with utter randomness. Few stable identities emerge. IRC seems to be one exception to this rule because, although free, it does seem to have stable and regular identities. Yet it’s missing the kinds of tools that promote identity formation—there are no profiles.

Jonathan says, “Oddly enough, speaking of issues of isolation and connectivity, even in a large community of queers, I’m surprised at how much I want to communicate with queers specifically in online spaces.”

Keith says [to Jonathan], “I agree: It’s more important for me to be online than to go out to the bars. I find the interactions more interesting.”

Barclay says, “Jonathan, New York City seems to be at the front of that shockwave—bars are dying even in the big city because queers meet each other online.”

Keith adds, I don’t think that’s happening in just the large urban areas. I know that in a relatively small college town like Lafayette, Louisiana (compared, anyway, to Chicago, where I grew up), I know many queers who never step into a bar and who mediate their entire gay lives online. For one thing, many of the gay men I know here are married, with children, and are very deeply closeted, even (or especially) from their wives. The amount of bisexuality in this part of the world amazed me till I realized that many of these were men who would be Kinsey sixes—almost entirely gay—except for the pressures that result from the social taboos against homosexuality and, more positively, from the strong desire of gay men to have families. [Kinsey sixes are those men who identify as entirely and only homosexual on the Kinsey scale made famous by Alfred Kinsey and his colleagues in the late 40s and early 50s; a six would be homosexual both in terms of genital activity and in one’s fantasy life, including dreams (National Consortium of Directors of LGBT Resources in Higher Education, no date).] In fact, one of the issues controlling safe sex and HIV transmission is the lengths some men will go to avoid becoming HIV positive, even more than in big cities. This is doubly the result of how hard good medical care is to get for HIV (I drive two hours to New Orleans to see my specialist) and to ensure that, if they so desire, they can have biological children of their own.

Jonathan says, “Yes, yes, more than this, though...I think that, for me, the online space takes away some of the body consciousness that seems to permeate gay, male culture and interaction.”

Barclay says, “Depends on which gay male culture, of course.”

Barclay adds that while there is a body conscious segment of gay male culture, there’s also the bear community (focused on hirsute and husky men) and the chubby chaser community (focused on larger and overweight men) and, well, the gainer community (focused on actively gaining weight), all of which celebrate other kinds of bodies and cultures. Of course, Jonathan’s right on some level because these are all subcommunities, and there’s even a body consciousness in a place like the bear community, which might celebrate “muscle bears” with hard guts and barrel chests over someone who is more simply overweight.

Keith says, “Oh yes: In bars, for instance, older guys can’t really talk to younger guys until they know them and they can’t know them till they talk to them. The barriers are much lower here (and by here I mean online).

Barclay says, “And it’s easier to have a conversation without loud bar music.”

Jonathan says, “the pleasures of the text...”

Jackie says, “Yes, although it’s a body consciousness that permeates all sorts of cultures; and face it, hey, there are acrobatics you can do here that you’d never do in RL [real life].”

RandyW agrees with Barclay, remembering that his online friend Legba once made this observation in Wired: “We exist in a world of pure communication, where looks don’t matter and only the best writers get laid” (Quittner, 1994, sidebar, para 11).

Jackie says, “I remember my first interactive online experience was a queer one—on AOL of all places. In 1995, I’d just gotten my new Mac Performa 630 and aol.com service.... I discovered the lesbian chatrooms on AOL. I was blown away—it was my first moment of AHA! AHA on the Internet—like oh, wow, I see what the big deal might be.”

Saffista says [to Jackie], “I discovered them on Prodigy back in the days of bulletin boards and chatrooms.”

Saffista wonders how much of what she does online now extends from exploration done only before one actually comes out.

Angela [Crow, Georgia Southern University—Statesboro] says, “What do you

mean, Saffista?”

Saffista says [to Angela], “Before I came out I built an online community to prepare myself for RL. Now that I am out I still depend on VR [virtual reality] for community now that I am in the sticks.”

Barclay says, “The same is true even without the sticks, Saffista.”

Saffista smiles at Barclay.

Barclay smiles back.

Angela says, “So the web was part of the coming out process for you?”

Saffista says [to Angela], “Yep. It gave me a space to contemplate my feelings. Online I was able to experiment with my queer identity. I learned that it was actually okay to be a ‘tomboy’ and that I looked like I was in drag when I wore a dress because I actually was! I came to realize that no matter how many times my cousin tried to teach me to mimic them, the ‘girly’ hand gestures just wouldn’t work for me. It was all a question of performativity and ‘performing the femme,’ this femme which is not one. I came to understand what Judith Butler (1990) meant when she said, ‘gender proves to be performative, constituting the identity it is purported to be. In this sense, gender is always a doing, though not a doing by a subject who might be said to preexist the deed (p. 33).’”

Barclay wonders how young the next generation of queers will be, and wonders what HE would have done with the Web at his disposal while a teen.

RandyW says, “In part I like meeting people online because I am master of the element, master of text.”

Keith says, “Yes, and people who don’t do well in cyberspace often don’t do well because they so fail at its rhetoric.”

Barclay says, “So THAT’S why composition matters—it gets you laid,” and smiles.

Keith laughs at Barclay’s line.

Saffista laughs.

Angela says, “I wonder how much our sense of queer locations online has to do with when we came out...(or when we will come out).”

Saffista says [to Angela], “Good question.”

Jonathan says, “Interesting, Angela.”

Barclay came out pre-Web, but just barely.

Jonathan says, “Me too.”

RandyW came out pre-PC.

Keith is older than most of you, he thinks, so he was out way before the Web, but the Web has certainly changed how he is out: In my youth, there were, practically speaking, three options: bars, baths, and parks. All three were highly sexualized and all three assumed (especially the baths and parks) that talking would lead to sex. Or even that talking was not allowed. One thing online communication has changed radically is that men can now speak to men they’d never speak to in the bars. The social barriers between races, between “hot” men and “dogs” or “trolls” and between younger and older men are much lower online, because one can chat without the automatic assumption that one is looking “to trick” for a sex partner for that night.

Jackie came out in 1984.

Jonathan says, “1989”

Barclay says, “1988ish”

Saffista says, “the early 90s”

Keith says, “Ready for this? 1975”

Barclay says, “whoa Daddy!”

Keith says, “You bet, Boy.”

Barclay says, “I was 5.”

Barclay laughs.

Barclay adds, maybe 4 even, depending which month you came out.

Saffista says, “I was 6.”

Jackie says, “I was 18.”

Keith glares.

Saffista smiles at Keith.

Keith says, “oh shush, y’awl.”

Angela says, “and aging becomes an issue for conversation.”

Barclay says, “How so Angela?”

Jonathan says, “It’s curious that, of all the things to talk about, we return to this seemingly most ‘basic’ question of identity.”

Keith says, “I think it’s way easier for queers to negotiate aging in cyberspace than in any other space. It’s not so readily available as information with which we can discriminate against one another.”

Saffista adds, this also leads back to coming out as an African American queer. I think it is easier to come out online where nobody knows that you are older, darker, fatter, etc., things that can make you less desirable on the bar scene. A place where the various layers of “otherness” can be hidden if one chooses, where one can “pass” by a simple act of omission. This is true in chat rooms and in MOO space. Chat profiles don’t ask for race and although I can @gender myself Spivak I can’t @race myself Black. In these spaces you have to make a concerted effort to @race yourself. [In order to assign your character a gender, you must use the @gender command in the MOO, but there is not command for assigning yourself a race. Assigning race involves incorporating it into the written description.] It must be written into a narrative description of yourself in MOO or as the cliché BGF [Black gay female] in chat profiles. In “Erasing @race,” Beth Kolko (2000) talked about this phenomenon of erasing race, which serendipitously leads community members to believe that:

the default race of the MUD is…White; attempts by users to mark race otherwise tends to result in confrontation…given a default, why choose to mark the “property”? An attitude that race is one of the things that purportedly can stay behind in the “real world” prevails; marking race online comes to be read as an aggressive and unfortunate desire to bring the “yucky stuff” into this protoutopian space. (p. 216)

And interestingly, it has been my experience that unless you are in an African American space online, you are expected to keep such “yucky” details to yourself unless there is a specific request or a specific expectation of disclosure.

Barclay says, “Although again Keith that depends on which community—some segments of the gay male culture value and venerate age (and experience).”

Keith says, “Right, and Daddy/Boy allows that seepage to occur; in fact, that set of roles allows aging to be not only ok, but in fact, hot. That [seepage] allows people to ‘practice’ different roles. I know many of my students, for instance, came out online well before they came out in real life.”

Barclay says, “I think that will be increasingly true, Keith.”

Keith says, “Yes, and HIV works that way too.”

Keith came out as poz [HIV+] online well before he came out as poz to anyone in real life except close friends, partner, and family.

Barclay says, “Good point, I imagine that’s multiply true—some, for example, may come out as kinky or as bears online first.”

Jackie says, “Age? I think, actually, that it’s a particularly queer question of identity...not just age, but ‘when did you come out.’”

Angela says, “Well it seems our queer experiences online may be inflected through many age- related experiences.”

Jackie says, “Or ‘how did you come out...’ Another trope; the narrative of queer identity.”

Saffista says [to Jackie], “I think the how question gets dealt with a lot in RL too.”

Jackie says, “I think for me that points to a particular way in which online spaces and queer identities intersect.”

Jonathan says, “Yes, let’s go there, Jackie.”

Saffista says, “My coming out was much less personal, probably because of my online experience.”

Jackie says, “For me, identity has always been—at least as the ‘coming out’ story goes—a matter of narrative movement.”

Barclay says, “And the online world is a narrative world.”

Saffista nods.

RandyW says, “or many narrative worlds.”

Jackie says, “Oh, I dunno.”

Saffista says, “Mine was so driven by narrative that I told my mom with a book :-( It was the separation that text can give that made it easier. She was the first in my family to find out. After telling her and having discussions with some friends online about what a ‘weenie’ I’d been I just came out and told other family members (all puns intended).”

Jackie says, “I’ve been a practicing lesbian for a while... Practice makes perfect.”

Barclay and Saffista laugh.

Jonathan says, “But what’s perfection?”

Keith wonders if this leads to our second question:

Keith says, “Can you imagine being queer without technology or queer without the Internet?”

Jonathan says, “In terms of narrating my sexuality/sexual identity vis-a-vis the Internet… What you say about narrative movement, Jackie, reminds me of what Sean P. O’Connell (2001) said in Outspeak: Narrating Identities That Matter, ‘…it seems to me that the demand that one place one’s world before the other in language calls for a kind of double attention to the said. One must first attend to what one says, the story that one tells about oneself’ (. 129). Putting it out there, or ‘putting out’ online as it were, requires that we examine our own self-narration of queerness…and we may be able to do this online in ways that we can’t—because of homophobia and homophobic social conditions—in real life.”

Jackie says, “For me, the lesbian identity is not necessarily a cyber-intensive one, but the queer identity might be. Hmmmmm, I’m not sure if I even understood myself on that last one.”

Keith says [to Jackie], “That’s interesting. Can you expand on that?”

RandyW says, “I’m reminded of conversations with gay men of an earlier generation who said that WE had it so much easier because there were bars out in the open, student gay groups, etc. In one way, online spaces can be seen as an extension of those queer-identified spaces.”

Randy adds, for discussions of queer space, see the pioneering book Queer Space by Aaron Betsky (1997) and the essay collection Queers in Space edited by Gordan Ingram, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, & Yolanda Retter (1997).

Barclay says, “But the fact that we can even ask this question reminds me of a talk by Gayle Rubin (2003) that I attended recently. Rubin was discussing geologies of queer studies, and she used the metaphor of geology to suggest that new queer knowledges are built on top of old ones, like geological strata, which is just what Randy is talking about, on some level.”

Angela adds, I was struck by the way timing and location shape us and our expectations for the net. Because I’m always looking for aging threads in conversations, I was interested in Barclay’s mention of Gayle Rubin’s image of geology, the stratas, that metaphor. How we experience the Web may have much to do with when we made sense of our identities and the communities available to us at that time, both on- and offline. The net certainly shapes my ability to remain content in this small rural town: Any day of the week, I can listen to live broadcasts of radio stations more in keeping with my political bent from live feed on the Internet. My connections to other (distanced) humans are frequent (instant messaging) as I work through a grant proposal or think out an idea on queer. Phones or letters wouldn’t have provided me the resources I have now. This week, for instance, Victor Vitanza’s Pre/Text discussion on Massumi interrupted the writing of this text. I am focused on a conversation that couldn’t have happened in 1990. That my experience is not Rubin’s is not Keith’s and is not Jackie’s caused me to think about how complicated generalizations are about queer and technology. That I live a life I enjoy most days in rural, southern, Georgia is something of an accomplishment, I think. (This is not a region issue per se; I would say the same of rural, southern, Kansas.) I think about this issue of aging particularly in terms of my students and hope that they have the resources they need as they make their way through the challenges of understanding their identities, hope that they might use the online venue if it helps them to explore in virtual life what they aren’t quite sure about in real life.

Jackie says, “Well, if I followed my logic, and I’m not sure I can, then ‘lesbian’ seems fraught with a different politic/rhetoric than queer in that ‘lesbian’ draws more directly on the idea of strategic essentialism, and perhaps demands a certain solidity of ‘I am’, and queer does not.”

Jackie adds, for strategic essentialism, I draw on Gayrati Spivak’s (1985) “Subaltern Studies: Deconstructing Historiography.” Spivak looks at, among other things, “the retrieval of subaltern consciousness” in historiographical approaches; she sees such retrieval as “the attempt to undo a massive historiographic metalepsis…[and] a strategic use of positivist essentialism in a scrupulously visible political interest” (pp. 213–14). In composition studies, a similar strategy is described by Susan Miller (1998) in Rescuing the Subject; as I’ve said elsewhere, the intersection of temporary texts and available technologies leads to a strategically fictionalized stability that Miller called “textual subjectivity” (Rhodes, 2002, p. 128).

Saffista says [to Jackie], “Yes! Perhaps the Internet helped me bring it into being by claiming it. Although I think I can imagine being queer without the Internet, I don’t know how well I can imagine coming out without it.”

Saffista thinks…nommo. Nommo is the West African concept of words granting power, according to Janheinz Jahn (1990). For the Bantu people, nommo influences things in the shape of the word. All substances are vessels of the word. Nommo is the concrete entity through which the abstract principle magara, the union of the body and nommo, is realized (Jahn, 1990).

Saffista adds that it was the whole process of naming the thing that made it real. It was only once I could name myself lesbian that it became an actuality. It was almost as if I was a nonperson until that point, and I felt no sense connection to those in the GLBT community. I was online where the named thing first became embodied and then later I went offline. I think that we, as scholars, tend to ignore the fact that the power of the word lies not only in the power to name but also in the connection it builds between speakers/writers and communities. In The Dialogic Imagination, Mikhail Bakhtin & Michael Holquist (1981) wrote:

Language is not a neutral medium that passes freely and easily into the private property of the speaker’s intentions; it is populated—overpopulated with the intentions of others. Expropriating it, forcing it to submit to one’s own intentions and accents, is a difficult and complicated process (p. 33).

Language is directly connected to one’s personal and cultural life. Not only do we speak and write our queer selves into being (nommo), but we use the same language to speak and write ourselves into community. I don’t know that this differs vastly online or offline but, for me, it was the (re)creation of self and the building of community online with the written word that bridged and eased the process offline. I had already used the generative power of language to become who I was most comfortable with at the time. This is not to say that after coming out online everything came easy, but it is to say that it may have been made easier by the fact that I had a better sense of who and what I was.

Saffista changes her name to Lesbian.

Keith can remember what it was like—I was out years before I started doing bulletin boards and IRC

RandyW nods enthusiastically and annotates a book about gay life in the South that talks about the role of highways and cars in rural Mississippi.

The book is Men Like That: A Southern Queer History by John Howard (1999). In addition to offering a corrective to the view that gay life post-WWII existed only in large metropolitan areas, Howard talked about ways the automobile served as a mode of communication as well as transportation, allowing gay men to meet each other across class and racial lines that would have been unthinkable in their home communities: “For some queer Mississippians, such freedom necessarily was found very close to home, just down the road a bit” (p. 110).

Barclay says, “So, before chat rooms, there were bars. Before homepages and emails, there were personal ads and letters. Before the gif, there was the actual photograph. Before the newsgroup, there was the club. Before porn sites, there were magazines and videos. What we do online may feel (may even be) new, but built on what came before. And so I’m reminded too of Neil Bartlett’s (1989) Who Was That Man?, Tzvetan Todorov’s (1976) The Origin of Genres’, and Denis Barons’ (1999) From Pencils to Pixels, all of which meditated to some degree the linkages between what is and what came before.”

Barclay adds Bartlett (1989) traced this geological strata in gay male terms; Baron (1999) focused on composition and technological literacy and was centrally concerned with the idea that “New communications technologies, if they catch on, go through a number of strikingly similar stages” (p. 16); and Todorov (1976) played out a similar argument in terms of genres, concluding that genres emerge “quite simply, from other genres” (p. 161). In all these cases, there’s a sense of continuity located in change. Similarly, it’s very different to be queer with the Internet, but those differences are located within genres of writing and reading that are remarkably the same.

RandyW says, “Before Gay.com—there were M4M rooms on AOL—I’ve always had a theory that M4M started as code to avoid AOL’s content controls—or is it just telegraphic language?”

RandyW has a similar theory about “boi.” The theory goes like this: In the gay male community, “boy” has a generous upward range, into the mid-twenties, at least. (See the previous use of the word in this conversation, for example.) It has less of the sexist and pejorative connotations of calling a young woman a “girl.” Nevertheless the concern about protecting underage online users means that using “boy” to denote a gay chatroom on AOL, for example, would be prohibited. “Boi” (by coincidence a Middle English variant spelling) thus avoids this proscription and has the additional value of suggesting that it describes something other than a child. From there, it has picked up connotations of hip, cyber, and stylish. (Or so goes my speculation.)

Barclay says, “Pig, too, is a term that has involved in relation to online content pressures and the general need for telegraphic language to save keystrokes online. My understanding is that it started as a term for men into ‘raunchy’ play such as coprophilia (sexual play with excretment) or urolagnia (sexual play with urine), but like ‘boi,’ it increasingly circulated out of its original context to become something more generic; coming to be associated with anyone who ‘can’t get enough,’ such as sex pigs, bondage pigs, boot pigs, and more.”

Keith says, “You mean all those are codes that get past parental controls? If so, that’s interesting, but I think it goes beyond that; those positive labels always name something distressing to the gay community and refigure them in such a way as to be acceptable.”

Keith adds that the easiest place to see this is with age: Intergenerational sex, even when legal—say consensual sex between a twenty year old and a sixty year old—would be described as occurring between a chicken and a chicken hawk, or between someone who is merely “hot” (because with the exceptions Barclay mentioned, young is hot in the male community) and a “troll,” a man who is undesirable merely because he is older. But call them “boy” and “daddy,” and that which was forbidden becomes marked by a set of socially defined roles in which such forbidden desires are not only allowed but approved.

Barclay says, “I’ve always wondered [where M4M came from], Randy, but now it circulates beyond AOL.”

Keith thinks it might have to do with the helping professions and sociologists and the label MSM (men who have sex with men), thus avoiding the label “gay.”

Keith says [to Barclay], “Does the Internet allow us more scope than other gathering places did? I know as a rural queer (it’s so strange for me to embrace that but I realized it was so the first time I agreed to drive an hour to meet a friend for lunch without thinking of that as unusual) without cyberspace my life would be much less rich.”

Jackie says, “I think the bar—>chatroom movement is interesting, as are the other movements Barclay refers to. But I’m always reminded of the weird and different ways gay men and lesbians structure their bars.”

Jackie shudders at the memory of all those lesbians slow-dancing to Melissa Etheridge.

Saffista likes Melissa Etheridge, still.

RandyW shudders at the memory of waiting for the one slow dance they played at 1:50 am, just before the bar in Baton Rouge closed.

Keith laughs and sways to “Last Dance, Last Chance for Love.”

Angela says, “So Jackie, is the lesbian identity the lived in-real-life-identity? and the queer identity lived on the screen?”

Jackie says, “Actually, I think that queer life online helped me expand my own sense of

sexuality. I more readily play with queer theory now, although I identify much more—for political reasons—as lesbian.”

Jackie adds that again, for me, it goes back to Spivak (1985) and Miller(1989); naming myself as

“lesbian” works strategically “in a scrupulously visible political interest, even though I’m perfectly aware that claiming that “stable identity” is of course fiction. However, I’m troubled by how easily the idea of “queer” has been assimilated and de-sexualized (disembodied) in mainstream culture and in academia, and I think that it’s at this rhetorical moment that LGBT folk need to assert that fictionalized, strategic identity.

In mainstream culture, we have TV shows like “Queer as Folk” and “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy,” neither of which troubles notions of sexual identity, and neither of which really challenges stereotypes of LGBT folk. “Will and Grace” and its desexualizing of LGBT people has already been analyzed quite a bit, I think. In academia, I’ll just point to last year’s Feminism(s) & Rhetoric(s) conference, where Jonathan and I presented “Feminism’s Erasure of the F***ing Queer Body” (2003). Out of the several days of presentations, only two presentations explicitly used the term “lesbian” or “dyke” in their titles (they were in the same session), while a number of others used the term “queer,” usually for the purposes of reading or queering written texts.

Obviously, our own panel was guilty of using the sexy theory term (queer), but we were trying to use it—quite explicitly—to bring up the idea of bodies and sex and materiality. By the time we presented (on the last day of the conference), I was quite aware of the event’s erasure of lesbian, gay, bi-, and trans- subjects (in the term’s several senses) and its rather safe co-optation of the term or subject queer. I realized the real political and strategic importance of being a lesbian in academia: I’m sure I annoyed people by the end of the conference because I found myself trying to start “lesbian: just say it!” chants at the banquet tables.

Jonathan says, “I’m intrigued by Angela’s question.... I wonder: Am I more queer on the screen than IRL? There’s a way in which I have a run-of-the-mill GAY life...”

Jackie nods at Jonathan.

Jonathan says, “...and then online I’ve found a variety of things that have turned my head, as it were, and that I’ve just had to try IRL.”

Jackie says, “Yes, I’m a much more exciting queer online than a lesbian in real life.”

Keith is the same way as a gay man.

Jonathan says, “And I’m not sure I would’ve run into those things IRL.”

Jackie says, “I’m much more queer online.”

Saffista says [to Jackie], “Why do you think that is?”

Jackie says, “The play of language and identity, the sense of possibility, of no bounds.”

Jonathan says, “the possibility of imagination...”

Saffista wonders if a sense of freedom might also contribute (for herself) to the knowledge that although I am wrapped up in my own online identity and how it affects my offline identity, that somewhere or somehow there is some separation.

Jackie says, “I think that online queerness pushes you to push; to follow your desires to (il)logical conclusions. I’m more of a flirt online; I’m more physical, believe it or not. I’m much more in my head in RL than online.”

Barclay is much more queer online than otherwise.

Angela adds, I wonder, after this conversation, if I had been a different participant had I turned queer later—would I have used this resource to explore? In real life, in the early nineties, plenty of safe avenues existed for exploration at the moment I was trying to make sense of queer, perhaps because I had the luck of good timing? The theory was hitting the shelf (literally) at the time I came out, and a gaggle of us (graduate students and faculty members at Kansas University) read and played together, exploring the boundaries of queer much more intensely in real life than I’ve ever experienced on-line. Jackie and Saffista made me think quite a long time about how my life might be different had I not had the shelter of my “real life” community. Would I have found chats helpful? Would I have explored that which I hadn’t explored in real life? Tried it out first online? I like the idea that the Internet provided and provides this resource for others. I also realize that my own experiences of real life shaped my sense of how to use the Internet now as a resource for queer—I literally use it primarily as a search engine, to find and maintain contacts with people writing interesting theory or creating riveting art.

Angela says, “hmm...and so the conservative lesbian encounters her queer self?”

Jackie says, “Well, I’d never describe myself as conservative really.”

Angela says, “I take back conservative.”

Saffista says, “As my freshman writers say about MOOs, no repercussions.”

Jonathan says, “That’s not true.”

Saffista says, “What’s not true, Jonathan?”

Keith says [to Saffista], “But there are repercussions; you know how it goes when things get said that ought not to be said.”

Jonathan says, “I don’t think these are spaces w/o repercussions.”

Saffista says [to Keith], “True, but at times it feels as if there are none, especially for people who are new to online spaces or who are not coming to the space looking for anything (dare I say) ‘real.’ Many times they don’t stop to think that there is an organic being behind the representation that they see on their screens. A raced, gendered, sexed organic being. This is where problems can really arise, when people don’t feel that there are any repercussions for their actions toward people. <naïveté> Slurs thrown about in cyberspace don’t count do they? </naïveté>”

RandyW says, “I think part of this labeling is this wonderful creative, self-expression that those of us in this room celebrate. But another part is the efficiency of the information age. People are looking for very specific kinds of information about potential sexual partners online—info that’s been relatively unavailable in real life.”

Saffista agrees.

Jonathan says, “Yes, and I wonder about that...is that what’s queer?”

Jackie says, “So in some ways, I’d say that online space—especially MOO/IRC space—embodies people.”

Keith says, “That’s odd! I’d agree about MOO, but NEVER about IRC.”

Angela says, “I’m sorry, I can’t remember the word you used above...”

Keith pasted in, “Jackie says, ‘Yes, I’m a very much more exciting queer online than a lesbian in real life.’”

Jackie says, “Ah, not conservative, Angela, just unexciting.”

Keith says, “IRC feels the most disembodied space of all.”

Jonathan says, “But to me, it’s extremely embodied... well, maybe not extremely...”

Jackie says, “My experience with IRC has been with people I know in RL, so that changes it a bit.”

Keith says, “That would.”

Jackie smiles.

Saffista says, “For me it has a lot to do with how connected I feel to that community: Is it someplace where I know and am known, or just someplace I am visiting. It’s just like offline space. I feel freer in spaces where no one knows me or has any particular expectations.”

Keith says, “Whereas for me, it’s an extension of the technology; MOO makes me most embodied of all.”

Keith catches a glimpse of himself in a mirror and says, not bad, daddio.

Barclay giggles.

Saffista says [to Keith], “This is true of MOOs because you have a ‘body.’”

Jackie says, “In my MOO life, I have better clothes...”

Saffista says, “and you verb :-)”

Keith nods excitedly.

Jackie pokes Jonathan.

Saffista verbs well.

Barclay says, “Do profiles construct bodies online?”

Keith says, “Pictures help.”

Saffista nods.

Jackie says, “Do they have to be real pictures?”

Keith says [to Jackie], “Of course not unless you intend to meet. Then they have to be!”

Keith adds that this opens a wider issue for me: Where do the lines between “truth” and “fantasy” begin and end? For instance, if one is a devotee of phone sex, in which the sexual act is consummated between two (or more) partners who do not have any reliable visual clues concerning their age, race, or even gender, except perhaps pictures exchanged before hand, what does it matter (and how) if one or both partners are not telling the truth about what sociologists call their “location,” so long as the fantasy is not disrupted via, say, a sudden disclosure of truth, or a desire to meet in real life that would necessarily disrupt the fantasy? Even for phone sex conversations that are practice sessions for future real life transgressions, the veracity of the two partners involved in the moment is not at stake. Indeed, from this viewpoint, the claim that “oh, everyone you meet in cyberspace is lying about their age and body type and looks” is sufficient to serve as a marker of innocence, if not actual naiveté about how cyberspace works: Why would that lack of verisimilitude matter?

RandyW says, “Our LGBT campus student group has begun holding online meetings (replacing some IRL meetings) to accommodate members who are not out enough to attend a RL meeting.”

Keith says [to RandyW], “That’s interesting, do they like it?”

RandyW says, “They’ve just started this semester, Keith. I’ll let you know. The group has an interesting cyberhistory—during a fallow period when a lot of the active members had graduated, the group was little more than a web message board for several years. It has now embodied itself again.”

Jonathan compliments Jackie on her attire tonight.

Jackie says, “You like the top hat?”

Jonathan says, “I like the jockstrap, actually.”

Jackie says, “Yes, I’m the Gender Wrangler tonight.”

Keith laughs at the idea of Jackie in a top hat and a jockstrap.

Barclay nods.

Saffista says, “Interesting picture there.”

Keith thinks another question may help.

Keith says, “We don’t automatically assume that technology is queer...but we know that we’ve attempted to use technology for queer purposes. What are those purposes? What are those rhetorical events? What are those compositional imaginings? Would we mark them as successful queer moments?”

Jackie says, “Well, most obviously, the community building for queer folk out in the sticks. I lived in Mississippi—I remember!”

Keith says, “I’m finding myself increasingly interested in online journals/blogs/spaces for queers.”

Barclay says, “I’ve been working on pride flags. I’m thinking of one kind of rhetorical event/compositional imagining that I’d argue is pretty uniquely queer: the pride flag. They’ve really exploded online, and each time I think I’ve seen them all I run across a new one. It’s a kind of composition that seems to rely heavily on technology because it’s easier to make a flag graphically than fabrically and because it’s easier to disseminate that flag electronically than materially.”

Jonathan says, “Ever show your students godhatesfags<http://www.godhatesfags.com>?”

Keith says [to Jonathan], “I did that just yesterday. I may have solved the class size problem with that site.”

Saffista laughs at Keith.

Keith says, “They were, thank God, appalled.”

RandyW says, “And so much more cost-effective than flying Fred Phelps in, Keith!”

Keith reminds everyone that due to the school board issue, Phelps was here [Lafayette, LA].

Keith and Randy reference the 2003 Marcus McLaurin scandal, in which a teacher in Keith’s home parish disciplined a young boy for merely mentioning that he had two mothers as he lined up for recess. This became an incident that received international coverage, involving as it did an intersection of queer issues with free speech issues, the right wing claiming it as a gay and lesbian issue that had no place in the classroom, the left wing claiming it as a free speech issue that had nothing to do with its queer content. In reaction to this, the infamous Rev. Fred Phelps of Westboro Baptist Church and owner of <http://www.godhatesfags.com> came to protest both the queer community and especially the two mothers (as sinners) and the Lafayette Parish School Board (because although it backed the teacher involved, it did not do a sufficient job of disciplining the student).

Jonathan says, “But would students be appalled if you took them to a radical fairie site, K-boy?”

Keith says [to Jonathan], “I think that would be more appalling to them. It’s ok to hate Phelps, but a radical site like that would be a space they wouldn’t know how to deal with. It’s so clearly ok or not ok for them. A very queer site, especially when I teach it, is barbie.com <http://www.barbie.com>.”

Saffista says, “This last question takes me back to my earlier response about VR helping with the coming out, affecting it in a very real way and then later becoming (once again) almost my sole source of gay community.”

Jackie says, “I’m wondering...when we talk about technology and queer issues, do we just mean online/Internet technologies?”

RandyW ponders Jackie’s question.

Randy adds, I always have to ponder when someone brings up this issue. We’re so accustomed to thinking of technology as shorthand for “computer-related” that it can be tough to shift gears to think in a broader way. The changes that the car brought to the queer community in Mississippi are one similar effect. For me, the intersections between queer identity are so clear and compelling with online technologies that I have trouble seeing similar issues in technology more broadly defined. For example, is it significant that I’m listening to The Communards on my iPod while I write these annotations? It’s comforting and it puts me in the right mental space for thinking about some of this; perhaps the technology helps me to carry my personal queerspace around with me more easily. RandyW continues to ponder.

Jonathan says, “Jackie, of course, technology has been helping us queer sexuality for quite some time...like the birth control pill!”

Keith says [to Jonathan], “Telephones too.”

Saffista thinks back to performing the femme on the phone for practice and profit and wonders how telephones and telephone-mediated sexuality gets further queered by performativity. She then decides that this is material for another article.

Barclay says, “Good point, Keith.”

Jackie says, “Because I’m thinking of my strange play with Photoshop—Jonathan’s seen some of this—and it’s led to some of my most queer moments. I posted a picture of myself on my office door. It was my head on a semi-nude male body. Actually, he was just shirtless—but he had a big old belt buckle. What was interesting is that it really freaked some people out.”

Figure 1

Jonathan says, “It was hot, because it looked so real!”

Jackie says, “The combination of intimacy—we know Jackie’s face—and distance—that’s not her body.”

Keith says [to Jackie], “Things that blur boundaries are always dangerous.”

Jackie says, “Desire—that body is hot—tempered by but wait, that’s not Jackie.”

Keith says, “And male and female... probably particularly dangerous in a lesbian, I would guess.”

Jackie says, “Or is it hers? Do I feel attracted/disturbed by my attraction/disturbance?”

Keith says [to Jackie], “And especially do I feel interested in the tensions between the two halves of the picture.”

Jackie says, “And I don’t think it would have been nearly so disturbing to people if I’d pasted my head on a female body; but there’s the notion of the lesbian as male/female/neither/all.”

Jackie says, “Queer, in other words.”

Angela says, “How would you define a queer moment?”

Jonathan says, “Queer moment: when your sense of your own possibilities for intimacy are stretched beyond the heteronormative imperative but people who fool around with technology, particularly communication technologies, have been doing that for some time...”

Keith says [to Angela], “For me, the queer moment is when a queer takes a text that may or may not itself be overtly queer and reads it in a way that breaks beyond compulsory heterosexuality. Any site can be queer. Adrienne Rich (1981) named a category she called compulsory heterosexuality; she argued that heterosexism is so pervasive that it becomes absolutely normative and tends to inscribe itself over other categories. On the one hand, then, heterosexuals get to be open about their status in ways that don’t even seem linked to heterosexuality, as when a married women talks about ‘her husband’ in an entirely nonproblematic way but, on the other, my mentioning my partner in a relationship that has lasted seventeen years brings on charges of being ‘obsessed with’ or ‘flaunting’ my sexuality.”

RandyW says, “The point of this book that I can’t remember the name of is that the technology of the car (and the road) affected gay male social/sexual connections in Mississippi.”

Barclay says, “Have people seen Obscene Interiors (Jorgenson, 2004)? It does just that kind of work.”

Barclay adds that it will have come out in book form in April 2004, but you can still get a sampling of it on the web at <http://www.justinspace.com/obscene/oi1intro.html>. The basic idea is both simple and brilliant: Take men’s naked self-pictures (the ones doubtlessly sent to potential sexual partners on the web), cut out the men, and then critique the interior design. It’s a perfect example of what Keith described as a queer moment—the pictures themselves may or may not be queer, but the campy critique of interior design provides a definitely queer reading.

Figure 2

RandyW says, “Yes, Jonathan—I’m thinking of all the Tolkien/technogeek connections going back years and years.”

Randy adds that the first time I went online at Chapel Hill in the mid-80s, we had to adjust a Gandalf box to make the connection work. And as we know from Arthur C. Clarke, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” (Stepney, n.d.).

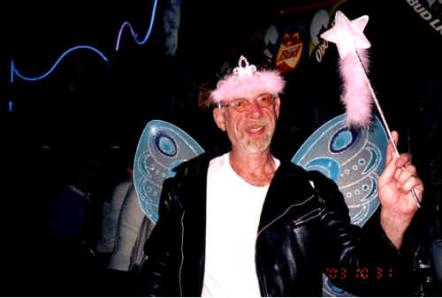

Keith has pictures of him in half drag from Halloween: he was Fairy God Daddy.

Keith says, “Big wings, a pink wand, a tiara and a leather jacket, blue jeans and big ol boots.”

Barclay says, “What kind of boots?”

Barclay smiles.

Keith says, “Brown work boots.”

Barclay says, “Good enough.”

Jonathan says, “Très trans...”

Figure 3

Jackie says, “So to pat myself on the cyberback, it felt like I was contributing to little frissons of queer desire in the office...”

Barclay pats Jackie’s back.

Jonathan says, “Jackie’s comments link back to an earlier comment about the technology allowing us all the more effectively to create sites in which we disrupt our own desires...”

Jonathan adds, Deborah Britzman (2000) once wrote “Making knowledge both strange and familiar is the work of learning and teaching. We must do both in order to live and to learn creatively, in order to elaborate our sexuality, in order to imagine the possibilities of citizenship” (p. 51). I’m hearing that’s what the Internet has allowed us to do…to “elaborate” our sexualities, perhaps in ways that challenge our own presuppositions of what is normal…

Jackie says, “So I guess what I’d say is that there’s a certain ease with technology—not just technology itself—that lends itself to play, and perhaps particularly queer play.”

Barclay says, “‘ease’ after the learning curve.”

Keith says, “Ah that’s right, that’s right. It’s queer to manipulate space in this way, which leads to the final question: What, if anything, has cyberspace done to our conception of writing, of writing queerly, including the kinds of writing we do for the World Wide Web?”

Jonathan says, “Is there something fundamentally ‘queer’ about the technologies...their ability to put us in touch with networks of people?”

Barclay says, “Hence Obscene Interiors—very queer kind of writing.”

Barclay adds, and queer in a few ways. For starters, if we imagine these as the pictures of gay men (possible) then the ‘reading’ of the picture reveals the ways in which a self-picture is part of a process of self-composition. The self-picture becomes a queer genre when we start caring about the background as much as the subject. At the same time, reading the interior design not only reveals the picture as a compositional process but also celebrates traditionally gay and queer discourses such as camp and interior design.

Jackie says, “Well, maybe I’m just speaking as a closet 18th century sort, but I think it’s

brought back the notion of wit—wit as the marker of strength, of language as

something manipulatable and powerful, a way of claiming space that may not be

available to us in RL.”

Jackie adds, as Joseph Addison (1711) wrote in the Spectator:

As true wit generally consists in this resemblance and congruity of ideas, false wit chiefly consists in the resemblance and congruity sometimes of single letters, as in anagrams, chronograms, lipograms, and acrostics; sometimes of syllables, as in echoes and doggerel rhymes; sometimes of words, as in puns and quibbles; and sometimes of whole sentences or poems, cast into the figures of eggs, axes, or altars: nay, some carry the notion of wit so far as to ascribe it even to external mimicry; and to look upon a man as an ingenious person, that can resemble the tone, posture, or face of another. As true wit consists in the resemblance of ideas, and false wit in the resemblance of words, according to the foregoing instances; there is another kind of wit which consists partly in the resemblance of ideas, and partly in the resemblance of words; which for distinction’s sake I shall call mixed wit. (para. 3)

Modern technologies of writing, particularly network technologies, let us “play” with language in ways that might trouble Addison—wit online often occupies the space between true wit and false wit. The technology itself, and its capacity to use design, emoticons, puns, even the play of MOOspace itself—those factors create a capacity for what I would call queer wit online, neither true nor false, and closer to Addison’s idea of mixed wit.

Keith says, “I think my ability to joke has really helped my status in the gay community here in Lafayette. I mean, an older gay guy with HIV? I should be invisible! Being the faculty advisor to the student LGBT group in a university town helps too of course.”

Keith adds, but perhaps not nearly as much as my visibility in a gay chat room: In my four years in Lafayette, and at 46, I find myself almost an older statesman of the statewide virtual gay community, mentor to many young queers who have no one else to talk to about their sexuality, and a sounding board for various concerns about HIV. My position as an open-minded queer who is both a devout Christian and openly HIV-positive puts me at the edge of boundaries in a way that simply doesn’t exist for much of Louisiana’s queer community. It’s my online presence, as much as my work at the university, that has made me known state-wide and privy to much information, especially about who is HIV-positive (a taboo category here) that I otherwise would not have.

RandyW is reminded of all the seemingly queer referents in LambdaMOO, the “mother of all MOOs.”

Keith says [to RandyW], “It’s been years since I’ve been there. What referents?”

RandyW says, “Well, the name for one. New guests enter by coming out of a closet. And there’s some Wizard of Oz, as well. But as I understand it, the creator said there was not an explicitly queer agenda.”

Randy adds, “For example, when a user chooses to go to his or her defined ‘home,’ the program supplies a message about clicking one's heels three times, just as Dorothy did to go back home to Kansas.”

Keith always wondered about coming out of the closet in Lambda.

RandyW says, “And while there was a significant gay presence there, Keith, it was not the dominant community.”

Keith says [to RandyW], “It sure wasn’t!”

RandyW adds, see Josh Quittner (1994) for a description of the author’s experience of LambdaMOO.

Jackie says, “And I realize that maybe this is a MOO cliché, but what about gender play?”

Keith remembers a night at connections in MOO which we all gender shifted.

Jackie says, “I can be a man? A woman? Well, no, but....I can pick pronouns.”

Barclay says, “That’s true of chatrooms, too, yes Jackie?”

Jonathan says, “It’s true of web pages!”

RandyW says, “How many genders do you want, Jackie? We’ve got tons!”

Keith says, “And not just gender; chat allows one to be anyone..”

Jackie says, “So in some ways, we’re aware that the play is going on, that a she may not be an ‘embodied’ she, but many different genders....”

Saffista says, “It gives you the opportunity to experiment, to explore, to perform different gender roles. Makes me think of Ralph Ellison’s (1995) Invisible Man. Perhaps on many different levels I am that invisible man online, literally and figuratively. Invisible in that my racial and sexual markers can not be seen but can be read and invisible in terms of avoiding detection in the above ground/offline world until I am ready to disclose my new/true identity. And able to maintain that invisibility for only so long because ‘there’s a possibility that even an invisible man has a socially responsible role to play (p. 39).’”

Saffista is big on exploration.

Keith pastes,

Available genders in MOO space: male, female, Spivak, either, splat, none, or royal.

Saffista smiles.

Jonathan says, “That’s the disruption of desire...”

Jackie says, “Such an easy way to show the explosion of gender. Pow..”

Barclay nods.

Jonathan says, “I can talk dirty to someone, hope it’s a man, but feel all the more frisson because it might not be...”

Jackie says, “Yes, that was me the other night, you bad boy.”

Barclay says, “But I usually assume the men I chat with online are, indeed, men—there are textual clues.”

RandyW had a multi-year friendship with someone online—and to this day is unsure of the person’s gender.

Jonathan says, “How much do we project into those textual clues, Barclay?”

Barclay says, “Good question, Jonathan—I’m not sure.”

Jackie says, “I’m not sure if I ever learned any social realities from time online—it’s so different out here. :) I’m different online; I react differently; I shape others’ reactions differently than I might in RL—so hard to tell.”

Saffista says [to Jackie], “That’s true, but it can make you feel more secure knowing the possibilities.”

Keith knows a guy who tested being HIV+ by coming out as HIV+ in chatrooms first even though he wasn’t, then bug-chased till he went positive. He said he wanted to be sure he could deal with the social realities of being HIV-positive first by trying it out online. That’s an extreme case, but it’s true.

Keith adds, Bug-chasing identifies a practice in which HIV- men, for a number of complex reasons, seek out HIV+ men for unsafe sex with the explicit purpose of sero-converting, that is, of becoming HIV+. These reasons range from a lack of self-esteem to an inability to deal with the huge stresses sexually active HIV- men face in playing safe for a lifetime, including the losses of intimacy caused by a lack of exchange of bodily fluids.

Barclay says, “Whoa.”

Keith also knows a set of twins in Lafayette who went transgender online first and are now both getting ready for sex change operations in real life.

RandyW didn’t know Lafayette was such a hotbed of sexual experimentation. “People used to just go to the New Orleans’ French Quarter.”

Keith says, “oh yes, it’s the long history of drag here”

Barclay laughs and remembers the Quarter.

Keith says, “Quinten Dronet, a member of the gay community here in Lafayette, tells me that he remembers a tradition in which drag queens gave up drag for Lent and grew beards, then cut the beards off for Easter and went back to dresses...”

Barclay believes it.

RandyW is speechless with delight.

Barclay says, “A costume culture.”

Keith says, “It’s very much a costume culture here... one of the two times in my life I’ve done drag was here, because I figured, hey, who would possibly mind?”

Barclay says, “It was no big deal to do it in New Orleans—and that was gendered drag or leather drag—it was all drag.”

Keith says, “Now everyone practices all this stuff online first!”

RandyW passes out costumes.

Jackie grows a beard.

Jonathan shaves his legs.

Keith puts on a midnight blue cocktail dress and pumps.

Barclay keeps all his body hair.

Keith pastes, @gender female Gender set to “female.” Your pronouns: she, her, her, hers, herself, She, Her, Her, Hers, Herself

Keith says, “There! In the real world that would take months!”

Keith adds, what I had just done was transform my own online persona in the MOO (usually male) into a female, with a single command. Now, how this is read depends on how one thinks of the MOO body. I think of it as very real, as very embodied, and therefore the switch was, in that context, real. If you think of the MOO body as other than “real,” whatever that means, all I did was change the pronouns that were associated with my character; in other words, the MOO would now say “she” and “her” rather than “he” and “him” when referring to my character. In the real world, were I transgendered, I’d have to go through a year of hormone therapy and pass as a woman in daily life while working with a psychiatrist before I would be allowed to undergo an operation that would transform my physical body to conform with my own gender identity.

Barclay says, “You go girl!”

Jonathan shaves Barclay’s body hair.

Barclay says, “Jonathan will pay for that.”

Barclay smiles evilly.

Keith says, “Well, it’s been an hour, and we’re moving toward Mardi Gras!”

Jackie pastes Jonathan’s hair on as a big handlebar mustache.

Saffista laughs.

Jonathan is delighted...at the thought of the handlebar mustache...and possible future punishment.

Keith laughs.

Barclay says, “Laissez les bon temps roulez.”

[log closed]

Alexander, Jonathan, Gil-Gomez, Ellen M., & Rhodes, Jacqueline. (2003, October). Material Rhetorics: Feminism’s Erasure of the F***ing Queer Body. Feminism(s) and Rhetoric(s) Conference, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

Addison, Joseph. (1711, May 11). The Spectator No. 62 Retrieved February 23, 2004, from <http://www.mala.bc.ca/~lanes/english/engl201/spec62.htm>.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M., & Holquist, Michael. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Baron, Dennis. (1999). From pencils to pixels: The stages of literacy technologies. In Gail Hawisher & Cindy Selfe (Eds.), Passions, pedagogies, and 21st century technologies (pp. 15–33). Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

Bartlett, Neil. (1989). Who was that man?: A present for Mr. Oscar Wilde. London: Serpent’s Tail.

Boykin, Keith. (1996). One more river to cross: Black and gay in America. New York: Anchor Books/Doubleday.

Britzman, Deborah P. (2000). Precocious education. In Susan Talburt & Shirley R. Steinberg (Eds.), Thinking queer: Sexuality, culture, and education (pp. 33–59). New York: Peter Lang.

Butler, Judith. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

Ellison, Ralph. (1995). Invisible man. New York: Vintage International.

Howard, John. (1999). Men like that: A southern queer history. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ingram, Gordon Brent, Bouthillette, Anne-Marie, & Retter, Yolanda. (Eds.). (1997). Queers in space: Communities/public places/sites of resistance. Seattle, WA: Bay Press.

Jahn, Janheinz. (1990). Muntu: African culture and the Western world. New York: Grove Weidenfeld.

Jorgenson, Justin. (2004). Obscene interiors. Retrieved February 24, 2004, from

<http://www.justinspace.com/obscene/oi11.html>.

Kolko, Beth. E. (2000). Erasing @race. In Beth. E. Kolko, Lisa Nakamura, & Gilbert B. Rodman (Eds.), Race in cyberspace (pp. 213–222). New York: Routledge.

Miller, Susan. (1989). Rescuing the subject: A critical introduction to rhetoric and the writer. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

National Consortium of Directors of LGBT Resources in Higher Education. (no date). Kinsey scale. Retrieved August 25, 2004, from <http://www.lgbtcampus.org/resources/training/kinsey_scale.html>.

O’Connell, Sean P. (2001). Outspeak: Narrating identities that matter. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Quittner, Josh. (1994, March). Johnny Manhattan meets the furry muckers. Wired, 2. Retrieved February 15, 2004, from <http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/2.03/muds_pr.html>.

Rhodes, Jacqueline. (2002). ‘Substantive and feminist girlie action’: Women online.

College Composition and Communication,54(1), 116–42.

Rich, Adrienne. (1981). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. London: Onlywomen Press.

Rubin, Gayle. (2003, December). Geologies of Queer Studies: It’s déjà vu all over again. David R. Kessler Lecture in Lesbian and Gay Studies. Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies, New York.

Spivak, Gayrati. C. (1985). Subaltern studies: deconstructing historiography. In Ranajit Guha, (Ed.), Subaltern studies IV (pp. 330–363). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Reprinted in Donna Landry & Gerald MacLean (Eds.). (1996). The Spivak reader: Selected works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (pp. 203–235). New York: Routledge.]

Stepney, Susan. (n.d.) Laws. Retrieved February 15, 2004, from <http://www-users.cs.york.ac.uk/~susan/cyc/l/law.htm>.

Todorov, Tzvetan. (1976). The origin of genres. New Literary History, 8(1), 159–170.

Warner, Michael. (1999). The trouble with normal: Sex, politics, and the ethics of queer life. New York: The Free Press.

Jonathan Alexanderis associate professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Cincinnati, where he also serves as Director of the English Composition Program. He’s addicted (productively, and safely, he feels) to his email and the Web.

Barclay Barriosis currently the Director of Instructional Technology for the Writing Program of Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey—New Brunswick. His dissertation (nearing completion) examines the implications of technology for writing programs at programmatic and institutional levels. Barclay has a passion for both Web and New Media design and enjoys spending a lot of time online.

Samantha Blackmon is a native of Detroit, Michigan, and is a recent transplant to West Lafayette, Indiana, where she serves as assistant professor of English at Purdue University. Her recent research projects look at how issues of race play out in computerized writing environments and focus on race and network theory.

Angela Crow, an assistant professor at Georgia Southern University, writes about aging and writing and teaches professional and technical writing.

Keith Dorwick is assistant professor of rhetoric and computer communications at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Dorwick is co-administrator of AcadianaMOO with Kevin Moberly. Acadiana is located at <http://acadiana.arthmoor.com/cuppa>.

Jacqueline Rhodes is associate professor of English at California State University, San Bernardino. She has published work in College Composition & Communication, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, and JAC: A Journal of Composition Theory.

Randal Woodland is an associate professor of composition and rhetoric at the University of Michigan–Dearborn, where he directs the writing program. He has published articles on the organization of electronic discourse and the online experiences of LGBT people.