May the #Kairos Be with You: Accessibility, Authdi, Veils, and Star Wars

Digital technology's ubiquity and the frequency with which communication is performed in online spaces has made kairos rhetorically significant in new ways. Today, we’re able to create and disseminate texts in a variety of mediums to a variety of audiences, both of which can be thoughtfully designed by rhetors. Digital spaces allow for a new kind of propitious time and place. We argue for a new form of kairos that is based on the ability to create timing and place that is most effective for a given argument: #kairos, or “hashtag kairos.” We use the Force, of the Star Wars universe, as heuristic for understanding this new form of kairos. After all, Jedis use the Force to anticipate and respond to the world around them much in the same way rhetors use kairos to enhance the persuasive power of texts.

Yoda or Master Jedi Obi-Wan Kenobi might have said, “May the Kairos be with you” instead of “May the Force be with you.” Calling on the Force—like kairos—means using it propitiously (i.e. in due measure) at the “right” time and in the “right” place. What Yoda and Master Kenobi communicate in our remix of these good tidings echo Master Rheti (our term for significant scholars in rhetoric and communication) James Kinneavy in his more direct claims (2002, 2000, and 1986) and in our paraphrase: "The Kairos is what gives a Rheti his power."

Or in Kinneavy's non-paraphrased words: “So you say, tell me where kairos is important, and I say to you, tell me where it's not important” (qtd. in Thompson 83).

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

77

Copyright © 2015 by The Intergalactic Council of Jedi Masters of the Force. All rights reserved.

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

And

I see it [kairos] as the dominant motif in disciplines related to our own. The concept of situational context, which is a modern term for kairos is in the forefront of research and thought in many areas. The phrase "rhetorical situation" has almost become a slogan in the field of speech communications since Lloyd Bitzer's article on the subject appeared in 1964. (83—84)

Though Rheti Kinneavy's call for an increased awareness of kairos and his observations on the concept seem to have occurred a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, “situational context” or “rhetorical situation” are still dominant motifs in the field of rhetoric, communication, and composition. We feel, however, that the way scholars, instructors, and theorists should imagine this concept and apply it is transforming—so that kairos has become a new kind of “Force” to be reckoned with.

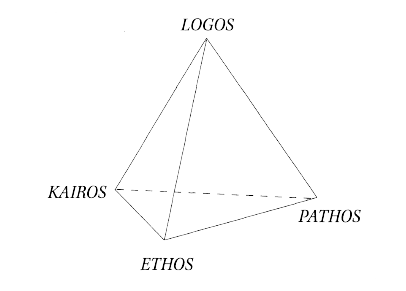

The application of kairos in rhetoric is very related to the application of Star Wars’ Force by Jedi. Michael Harker makes this connection implicitly: “Arguably, it [kairos] is where thought and theory converge with action” (84). We feel his “quadrangle” or “pyramid” needs a slight adjustment, however. It makes sense to us to explain it via the similarities between using kairos and using the Force.

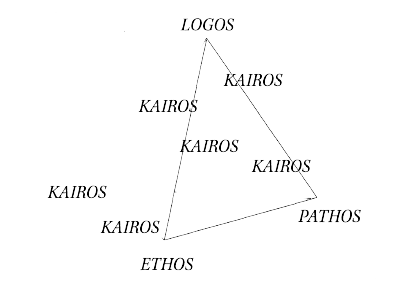

The informational and communication avenues mobile technologies and social media afford have evolved a new form of kairos: #kairos  (pronounced “hashtag kairos”). #kairos is the way in which kairos has become nearly omnipresent, “Forceful.” Unlike Harker’s visualization of kairos in which kairos seems isolated, static, and prescribed, kairos has become an everytime in an everyspace, accessible beyond privileged Jedis who were the only ones able to tap into the “Jedi Network System” (JNS). Kairotic opportunities—like the Force—are now everywhere and everytime. Rather than thinking of kairos as a discrete entity like ethos,

(pronounced “hashtag kairos”). #kairos is the way in which kairos has become nearly omnipresent, “Forceful.” Unlike Harker’s visualization of kairos in which kairos seems isolated, static, and prescribed, kairos has become an everytime in an everyspace, accessible beyond privileged Jedis who were the only ones able to tap into the “Jedi Network System” (JNS). Kairotic opportunities—like the Force—are now everywhere and everytime. Rather than thinking of kairos as a discrete entity like ethos, pathos, and logos, think of it more like this: “The Force [kairos] is what gives a Jedi his power. It's an energy field created by all living things. It surrounds us and penetrates us. It binds the galaxy together.”

pathos, and logos, think of it more like this: “The Force [kairos] is what gives a Jedi his power. It's an energy field created by all living things. It surrounds us and penetrates us. It binds the galaxy together.”

Figure 1

Figure 2

It isn’t as though using #kairos will result in Jedi-like telekinetic or precognitive abilities. Paying attention to the power of #kairos, however, can have profound effects on the ways rhetors engage with and understand communication and harness its “Force” or power. In what follows we ask you to “learn the ways of the #kairos” and enjoy our troping around kairotically with Star Wars as a way to describe and communicate the significance of #kairos in our current techno-rhetorical moment.

In “Episode 1: A New Kairos,” we describe in more detail how kairos is changing, develop the idea of a #kairos economy, and show how #kairos responds to these changes.

“Episode 2: Accessibility of the Clones” examines how #kairos is connected to a new model of writing and publishing that addresses multiple audiences through various media and language use, allowing a broader range of readers to successfully

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

decode what is otherwise potentially inaccessible for whatever reasons. “Episode 2,” furthermore, describes our use of two formats (this more traditional textual discussion and our non-traditional traditional infographic).

For “Episode 3: Return of the Authdi,” we describe the new form of author and audience—an authdience or authdi—that digital technologies have afforded. For us, authdience or authdi (author + audience) describes how the boundaries and binaries between authorship and audience-ship in digital media environments are blurring. In this episode, we describe the significance of this concept and how it connects to kairos. We show how #kairos aims to go a step further than providing the same information in various forms by allowing for debate and updates to a text after their initial publication.

“Episode 4: The Phantom Veils” argues for a shift in kairotic thinking and audience analysis away from the idea of surveillance towards an inclusion of sousveillance, coveillance, and selfveillance afforded by digital technologies. We argue that these veillances are important tools for gathering information and connecting with audiences. In other words, these are opportunities for not only generating knowledge and enhancing personal learning, but these veillances are also places to analyze, find patterns in audience engagement, and to build an audience. This episode, additionally, connects the different veillances to anxieties produced by digital technologies that are related to #kairos (FoMO and phantom cell-phone rings).

“The #Kairos Awakens” describes some of our issues with the Force and Jedi. It concludes our piece with an optimistic outlook on #kairos and how digital media (social media in particular) can be harnessed to be Force-like and, well, afford us abilities beyond the Force. While we explain our reason behind two formats in “Episode 2: Accessibility of the Clones,” we hope you read #kairotically and take into account your own everytime and everyspace. In more words, read what works for you, for your understanding/literacy, interest, and/or preference: read the infographic text, the article text, and/or shift back and forth between them. We’ve designed it for a number of situations.

Episode 1: A New Kairos

It’s pretty amazing that way back in the 1970s Star Wars sort of predicted social media with its JNS (Jedi Network System) powered by the Force. And it’s pretty amazing how rhetorical the Force can be, how it’s so very #kairotic: the Force is something to be used propitiously in a time and place. Like social media, opportunities to tap into the Force, to tap into #kairos, are always available. The Force and its relation to #kairos as a medium of communication connects really well to how Rheti Rhinegold thinks about technology:

The way we communicate today is altering the way people pay attention—which means we need to explore and understand how to train attention now, so that we, not our devices, control the shape of this alteration in the future. (14–15)

Rheti Rheingold might be speaking about digital technologies and distracting devices, but we think the theory applies to the Jedi, too. The Force is a kairotic medium where one is disciplined to concentrate on certain parts of one network like we do on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and LinkedIn.

We can think about kairos as invented or Invented Kairos—a term for creating

79

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

“propitious” or “right” time and “right” space for communication. This kairos is more about facilitating a decorum or creating a situation. We can see it happen when Qui-gon Jinn (who seems to be the sort of guy who would sell to drugs to minors) manufactures the importance of the pod race beyond just obtaining enough money to fix the hyperdirve of Queen Amidala's ship on Tatooine. He invents a situation—playing a game of chance—where he gambles with Watto for the rights to slaves (Anakin Skywalker and his mother, Shmi). Here Qui-gon invents kairos by generating this opportunity for “rescuing” the Skywalkers and relies on his knowledge of podrace gambling culture, knowing he can control the roll of the die to ensure “winning.”

We do the same things with social media. It’s when we create a website, a Twitter, a Facebook, a Tumblr, a Pinterest, for the Muhlhauser or Schafer or Blouke brand—we create opportunities for #kairos: to be timely, to be media and/or represented by and through it, to begin communicating. Starting a hashtag or beginning a conversation are ways to invent kairos—to invent opportunites for right time and space—or for reappropriating/repurposing an existing situation.

Invented kairos often goes hand in hand with awkward situations. Teacherly moments, for instance, are often the results of invented kairos. A colleague of Paul and Daniel's once invented kairos as a way to discuss the semiotics of t-shirts1. The opportunity arose when a student in a discussion before class or before the official teaching situation—honestly unaware of the shirt's meaning—asked, “What do you have that's bigger?” The student who asked the question was wearing a shirt that read, “Mine is Bigger.” Rather than letting it go, Paul and Daniel's colleague capitalized on the situation and invented a space to discuss sayings on clothing and how it relates to Shakespeare or how might a t-shirt with Shakespearean quotes be similar. The outside non-classroom conversation merged with the classroom context. It led to a discussion inspired in which a situation was invented or was off the traditional classroom script.

And while this is a crude example, Muhlhasuer and Schafer in their discussions of material rhetoric and gender differntiation among bodies, show how flatulence is often preceded by invented kairos2. So a person may invent a space for making this acceptable and/or kairotic by coughing. They also note that when a person who needs to excuse him/herself says

“I'll be right back. I need to get some cereal,” he/she is using a grocery store (tool) and words (tool) to invent a space and time where he/she can relieve the gaseous build up without his/her companions around. (Muhlhauser and Schafer)

Invented kairos is when one creates and uses opportunities for right time and right space.

Libby Miles was on the forefront of recognizing a rhetor’s power to construct propitious scenarios for given arguments. Miles notes, and we agree, that most scholars see kairos as something we “notice and act upon, when the moment is right” (746). She goes on to lament the fact that “scholarly considerations of kairos are rarely strategic” because kairos is seen by many as something over “which we have no control” (746).

Miles’ work— published in 2007—seems to reach into the future. By calling for an expanded understanding of kairos, Miles calls attention to the fact that rhetors are not merely lucky to encounter and act upon kairotic moments, but they instead can be crafted thoughtfully and applied. Miles observes the changing landscape of texts and

80

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

communication as they stood in 2007 and tells us that “we need different categories, new terms” and that “we need to reject a discourse so saturated in literary studies that it occludes our own intellectual traditions, suffocates future aspirations” (754).

Where we diverge from Miles, though, is that we believe kairos can be manipulated by rhetors to help create propitious times and places to argue for oneself and is not limited to creating such a scenario for another. Invented kairos is the scaffolding a rhetor performs to make a given action or argument appropriate for a specific time or place. Invented Kairos allows composers in digital spaces to see an audience and the context within which a text will be encountered, and to create a propitious time and environment for that text to be as persuasive and effective as it can possibly be.

Rheti Nathaniel Rivers makes an interesting observation about the nature of kairos. He says that “Kairos is something we compose, but we...do not do so alone. As Rickert argues, kairos is ambient and participatory. Good timing isn’t simply given nor is it simply made: it is complexly composed with others.” These composed situations, though, don’t necessarily have to be created on the fly.

So another concept Rheti padawan can try on is Situated Kairos—a term for pre-existing times and spaces for “right” or “propitious” communication explains a little more what Rivers and Rickert mean. This kairos is more about existing decorum and managing what is already there. Situated kairos describes how Rheti draw on cultures of use, which are “The conventions, norms and values for using a particular tool that grow up among a particular group of users” (Jones and Hafner 193). For example, Obi Wan used his specialized knowledge to determine that it was a good time, and that the Mos Eisley Cantina was the right place, to find a pilot.

We do the same things in social media—we follow certain people who tweet about particular things. If there seems to be a lot going on somewhere—like a trending hashtag—we try to become relevant and timely in that space by using it and entering the conversation. In teaching, situated kairos occurs when teachers and students negotiate the conventions of class decorum. It's the kairotic processes of pre-planned situations like activities, lectures, and discussion. Teachers and students are aware of this space as a situation for learning. Teachers, then, negotiate this space relying on their specialized knowledges to respond to students' questions and determine right time and right space for learning content. And students do the same as their learning is negotiated in whether or not something is indeed right time and place for making connections or having a new understanding, insight, or epiphany. Muhlhauser and Schafer offer this as another example:

Holidays (a cultural tool) are examples of situated kairos in general terms. Rhetors' actions in observing these days are highly situated or expected (e.g. a box of chocolates in a heart shaped box is not rhetorically appropriate for someone celebrating St. Patrick's Day).

Situated kairos is a collection of spaces that, as Rivers suggests, have been created. And these spaces can’t necessarily be created by the rhetor alone because they are part of a collective culture. The cultures rhetors step into (digital ones or in meatspace) have certain existing scenarios where situated kairos can be employed.

Our expanded definitions of kairos exist on a spectrum, of course. We aren’t really ever doing one or the other or the other completely—it’s not like the dark side/light side

81

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

binary. We use situated kairos and invented kairos simultaneously to create the right time and place for communication in online spaces. We just offer these terms for understanding how authors and audiences Using these kairos-es (kairi?) changes a Rheti’s relationship with time and audience. That change, or the difference between regular old kairos that the Jedi use and what we use in social media, is what we call #kairos (or “hashtag kairos” if you’re reading aloud). #kairos is the omni-presence- placence for kairotic opportunity in contrast to our previous examples where time and place are quite limited and controlled.

Another way to think about #kairos is how kairos exists in what Rheti Richard Lanham calls an attention economy. It’s that “theory that the basis of the new economy is neither material goods nor information but rather attention” (Jones and Hafner 192). Value is created from the exchange of attention. Seeking, paying, and obtaining attention has become important; it's more important than, say, a “stuff” or goods economy (as Rheti Lanham notes there is a plethora of stuff. Now, because goods and information are so abundant, an economy is fueled by attention or getting one to pay attention to your stuff or information or content.

Alex Iskold puts it this way when talking about the attention economy in the marketplace:

The basic ideas behind the Attention Economy are simple. Such an economy facilitates a marketplace where consumers agree to receive services in exchange for their attention. The ultimate purpose is of course to sell something to the consumer, but the selling does not need to be direct and does not need to be instant.

And he further notes:

It is important to realize that the key ingredient in the attention game is relevancy. As long as a consumer sees relevant content, he/she is going to stick around—and that creates more opportunities to sell. Literally, the longer a user stays on a site reading news etc, the higher the chance that person will click on an ad.

Value in the attention economy is dependent on #kairos, and wealth can be built in this economy by utilizing situated and invented kairos thoughtfully. In digital spaces users are asked to give their attention to numerous sources, but only some of these bids result in a transaction. Maximizing a rhetor’s effectiveness through awareness of various forms of time and place—in online and digital spaces—means that we’re engaging in an attention economy that depends on kairos—#kairos.

Episode 2: Accessibility of the Clones

Online, accessibility “means that people with disabilities can use the Web. More specifically, Web accessibility means that people with disabilities can perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with the Web, and that they can contribute to the Web ” (“Introduction to Accessibility”). And, as the W3C observes further in their discussion of accessibility, it has unintended benefits to those without disabilities to use the web: “Accessibility supports social inclusion for people with disabilities as well as others, such as older people, people in rural areas, and people in developing countries” (“Accessibility”). As part of their discussion of universal design, Lynch and Horton in

82

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

their recommendations for creating accessible websites praise how “the guidelines produced by WAI (Web Accesibility Initiative) and other accessibility initiatives provide us with techniques and specifications for how to create universally usable designs. They ensure that designers have the tools and technologies needed to create designs that work in different contexts” (Lynch and Horton).

Accessibility is, furthermore, connected to universal design principles in how it “incorporates access requirements into a design, rather than providing alternate designs to meet specific needs, such as large print or Braille editions for vision-impaired readers” (Lynch and Horton). Other examples include responsive design that works well on various devices rather than just one (i.e. a desktop or a smartphone) and alt-text that describes the nature or contents of an image.

We agree with the esteemed Rheti of “Multimodality in Motion: Disability & Kairotic Spaces” who argue for an ethics of accessibility: “a growing commitment—both intellectual and practical—to create texts that allow the broadest possible range of people to make meaning in ways that work best for them” (Yergeau, et al.). We want to avoid the kind of multimodal inhospitality that results “when the design and production of multimodal texts and environments persistently ignore access except as a retrofit” (Yergeau, et al.). Access should be an integral part of the composition process; “Those who design and produce multimodal texts and environments need to incorporate redundancy across multiple channels in order to make digital texts more—not less—flexible, and they should enable customization and manipulation of these texts by readers” (Yergeau, et al.).

And, of course, we support this kairotic endeavor. Implementing accessible designs and technical specifications is not only ethical, they are practical for web authors; in a sense they acknowledge that readers are not clones, are not identical to each other and have different needs. These practices attempt to avoid the privileging of “a particular set of preferences and modes of working” and instead strive to “anticipate ways that different users might be able to adapt texts and environments to suit their needs and preferences” (Yergeau, et. al).

In addition to this ethical imperative, from a #kariotic perspective, designing accessible websites is a way to increase audience access and opportunities to be the “right” time and the “right” place for more members of an audience. It’s a way to make the Force accessible to more people and, hopefully, get a message out and seen in more places and times. While this form of accessibility is definitely #kairotic, there is something missing which we think needs to be considered along with the technical affordances in designing accessible websites, one we think web authors should consider: designing with accessible literacy and audience constraints in mind.

Currently, accessibility is understandably focused on physiological differences in people’s abilities. However, accessibility discussions should also include a discussion of designs that are inclusive to different literacies and reading preferences. Rather than design one version of a text (which should, of course, comply with accessibility suggestions for the web and accommodate different screen sizes—mobile and desktop), rhetors should design multiple versions of a text (as we do here with the academic, the infographic, and the toggle texts). Such designs are not only ethical in accommodating different literacies, they are kairotic in how they allow one to reach more members of an audience, and, perhaps, more diverse audiences.

83

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

Patricia Bizzell’s concept of alternative discourse helps describe a few of the #kairos benefits of designing with accessible literacy in mind. These discourses (and the texts produced) “do not follow all the conventions of traditional academic discourse” and “exhibit stylistic, cultural, and cognitive elements from different discourse communities” (ix). To locate what might be considered alternative, find the traditional conventions of language, format, and/or genre of a discourse (i.e. find “the norm”), and then mix it with something non-conventional in language use, format, and/or genre.

Rather than trying to make a single text work for multiple audiences, web authors can write for multiple audiences by articulating research differently, taking advantage of the web as a medium for publication. Producing multiple versions of a text is not as time, space, or economically constrained as print tends to be. Rheti should compose media so it is accessible in multiple forms or make it what Henry Jenkins calls “spreadable.”

Spreadable media

refers to the technical resources that make it easier to circulate some kinds of content than others, the economic structures that support or restrict circulation, the attributes of a media text that might appeal to a community’s motivation for sharing material, and the social networks that link people through the exchange of meaningful bytes. (4)

So “A spreadable mentality focuses on creating media texts that various audiences may circulate for different purposes, inviting people to shape the context of the material as they share it within their social circles” (6). Making texts spreadable means they are being designed for circulation—for inhabiting a number of worlds, discourses, and/or literacies.

Jim Ridolfo and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss talk about this in terms of rhetorical velocity: “a conscious rhetorical concern for distance, travel, speed, and time, pertaining specifically to theorizing instances of strategic appropriation by a third party.” And we like this idea, too.

We want the velocity of our texts to be spreadable, or to spread the velocity. To do that, we think we should offer readers/viewers/listeners more than one way to encounter what at text. To circulate multiple formats which meet multiple audience needs and expectations is to be accessible and, as mentioned before, increase a Rheti’s kairotic “chances”—to be kairotic to sombodies, someplaces.

What if, for instance, the Force was articulated into a different genre? What if Luke Skywalker or Obi-Wan articulated his feelings into an infographic with salient points and less ambiguous descriptions of the Force? What if they offered an alternative that’s more understood by those in the discourse community? What if they shared this knowledge with those stormtroopers (clones) who lacked the medium of the Force and who didn’t have literacy in the Force? The privilege of Forceful knowledge would become #kairos accessible. It would have transformed into something that could be circulated more heavily and interpreted by a larger audience.

There are drawbacks to making spreadable content for authors, however. It takes more time to imagine, decide upon, and articulate pieces into different formats than it would to create a single traditional text and/or an alternative text. It may take more knowledge and skill of different genres and technologies to create. However, these moves are #kairotic and ethical and worth it.

84

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

By composing in multiple formats, an author is being more cooperative with readers/audiences rather than being directive or prescriptive. An author is cooperating with a reader by “exchanging information, modifying activities, and sharing resources for mutual benefit and to achieve a common purpose” (Himmelman qtd. in Rheingold 154). And both author and audience benefit: an author’s text is communicated and a reader benefits from having hermeneutic options for experiencing, understanding, and/or appreciating that text.

Audience members are not clones of each other. Besides physiological differences, audience members have literacy differences. While we agree with the reasons to make web content accessible technically, we also feel there is a #kairotic benefit and ethic for accommodating readers and creating texts that are truly texts in the plural, that pay attention to the accessibility of different literacies3.

Episode 3: Return of the Authdi

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away we became fans of Star Wars. We became fans on a spectrum that has a range. And our a-range-ment on this spectrum is not geek. We’re more of nerds. If you’re looking for a geek or a dork or a dweeb, then this isn’t the episode of our article you’re looking for.

As fans and nerds on this spectrum we remixed Star Wars culture: we “combine[d] or edit[ed] existing materials to produce something new” (Kerby). Paul remembers some of his first experiences as a remixer with his friend Mara Matthews in the 1980’s. They’d have Han Solo meet Barbie and My Little Pony. They’d fly the Millenium Falcon to Barbie’s Dreamhouse and transform the house into a veterinary clinic for Wookies and Ewoks. When they remixed, they negotiated storytelling and meaning.

In remixing Star Wars—when Paul played with Mara, when Cate officiated weddings between Boba Fet and a Snork, when Daniel’s cereal box X-Wing Starfighter crash landed into Hot Wheels traffic—we were doing something that was, importantly, participatory and transformative. We weren’t being authors exactly. And we weren’t being just audiences in these communicative spaces.

One might say our remixes were examples of prosuming (acting as both a producer and consumer) ("Prosumer"). We prosumed by consuming Star Wars (watching and buying the merchandise) and produced by being critics, creating our own stories, and circulating our ideas. In digital environments today, we prosume by blogging, posting on social media, commenting on each other’s work, and by remixing and sharing videos/podcasts/images/memes.

We might even be called produsers (productive users):

'Produsage refers to the type of user-led content creation that takes place in a variety of online environments such as Wikipedia, open source software, and the blogosphere.[1]' The concept blurs the boundaries between passive consumption and active production. The distinction between producers and consumers or users of content has faded, as users also play the role of producers whether they are aware of this role or not. (“Produsage”)

We create content when we bring together different people who know different things and we build on each others’ work: remixing. Adding a bit here. Deleting a bit there. Changing a few lines of someone else’s code to create something new.

85

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

We don’t really think those terms explain exactly what we do when we watch, comment, and play with Star Wars in a #kairos economy. In order to explain the exactly, we’ll do something intellifors (intellectual professors) and profesellects (professor intellectuals) like to do: remix words, or, portmanteau. Instead of “produsers” or “prosumers” we like authdience—to be authdis (partly because it rhymes with Jedis in our pronunciation of the word we just made).

Authdience—author + audience—is a different lens for taking into account the “new” relationship we have with authorship in digital media environments and observing how boundaries between the binaries of being an author and being an audience are blurring. To invoke authdience is to understand reader/writer relationships along the lines of Henry Jenkins in his prescient work published over twenty years ago.

Drawing on Michel de Ceretau’s work on reading practices and how cultural authority legitimizes particular practices and processes of reading/interpretation, Jenkinsexplains, “De Certeau’s ‘poaching’ analogy characterizes the relationship between readers and writers as an ongoing struggle for possession of the text and for control over its meanings” (24). For us, this ongoing struggle is connected to Barthes' concepts of readerly and writerly texts. Barthes “emphasized the extent to which the reader plays a role in the formation and comprehension of texts, and he demonstrated that the conventional view of the author as sole origin and generator of meaning was a false one” (Warnick and Heineman 85). A readerly text, for Barthes is “one in which the reader is to be only that—a consumer of the text designed by the author” (Warnick and Heineman 85). Readers or audience members are passive receptacles to be filled with content. Barthes’ also describes another type of text or way to view a text, a writerly text: “that someone who holds together in a single field all the traces by which the written text is constituted” (Barthes qtd. in Warnick and Heneman 85). Authdience emphasizes how readers or audience members are, in fact, authors: authors of interpretation; authdience emphasizes the writerly.

Much as we like the concept of produsage, the focus of authdience isn’t really about the blurring of consumption and production (prosumers) or professional and amateur blurring of content creation (produsers). Such terms are too loaded with economic connotations based in capital rather than communication or rhetoric. Produser and prosumer don’t take into account enough about feedback and adjusting and rewriting and recomposing. Produser and prosumer background another sort of relationship, the one which we’d like to foreground: the blurred relationship between author and audience.

We think authors are more connected to readers and reading processes than we often imagine. Authors are more like curators and remixers of texts than “original” or “authentic” creators. As Bahktin might put it, “Language has been completely taken over, shot through with intentions and accents…. Each word tastes of the context and contexts in which it has lived its socially charged life” (Bahktin qtd. in Jenkins 224).

Authors and audience members (authdience) are negotiators of intertextuality, that is, “when one text is in some way connected in a work to other texts in the social and textual matrix” (Warnick and Heineman 79). We feel there is an important change that has occurred in this matrix with regards to the digital technologies and the web’s affordances for intertextuality. Warnick and Heineman make a wonderful point regarding intertextuality and the web noting:

86

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

Thus, an observation recently made by David Natharius that ‘the more we know, the more we see’ (241) holds true. That is, the more literate users are about current events [or any events really], art forms, and cultural commonplaces, the more they will see and understand. But because intertextuality on the Web may pique user interest and curiosity and because the Web itself offers nearly unlimited opportunities for finding information, it could also be the case that the more users see, the more they will come to know. (94)

Still, we feel this is quite optimistic considering Richard Lanham’s notion of an attention economy.

Rheti Lanham contends that one consequence of the web is a profound excess of information. We’ve now got so much information at our fingertips that “we’re drowning in it. What we lack is the human attention needed to make sense of it all” (xi). So in order to compete for the vital resource of attention (from readers or viewers or authdiences), Lanham argues we have to make our work appealing; we have to attend to style. And for him that’s what rhetoric’s about—the attention that comes with style—rhetoric “tells us how to allocate our central scarce resource, to invite people to attend to what we would like them to attend to” (xii-xiii). Howard Rheingold coined a term that helps explain an important aspect of #kairos and its relation to attention. He argues that in a web environment “infotention” is an important ability to have. For Rheingold, infotention is “Intention added to attention, and mixed with knowledge of information-filtering tools, work together in a coordinated mind-machine process” (9). While Rheti Rheingold does not discuss propitious times and places, infotention connects with our notions of #kairos. Rheingold’s description of curation on the web:

People have always made choices about what to pay attention to. In the online world, they also make choices that influence what others pay attention to. That’s what people mean by the word curation in reference to online behavior. The curator role used to be reserved for the people who ran museums, but the term has been revived and expanded to describe the way populations of Web participants can act as information finders and evaluators for each other, creating through their choices collections of links that others can use. (127)

An authdi is a curator, a remixer, a sorter. Sometimes the sorting is more along the lines of the “writing process” and sometimes it’s more along the lines of the “reading process.” But regardless, these are active and equally transforming processes. If the goal of the authdi (though not all authdis may be interested in circulation) is to enact change, get a message out, and connect with other authdis, then #kairos is vital. It’s really about knowing how to be propitious during a time and a place.

Robert Scoble makes a number of suggestions for curators that are quite related to #kairos. He says, in this summary of an interview (italics ours),

- Find a lot of different viewpoints. (i.e. in searching viewpoints, one can find what is or might be propitious, be it linkbait or more fully developed ideas).

- Find patterns in streams that nobody else sees. (i.e. locating patterns is connected to #kairos as it can help authdis understand what’s working and not working, and it can even be used to find patterns of circulation—to increase timeliness and spaceliness)

87

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

- Share and distribute (works both ways for curator and for audience)4. (i.e. what sort of sharing is going to be propitious for this type of information. Where should I post it? Why should I post it here?)

- Find authority and know about sources. (i.e. think about who knows what and how are they perceived. Can I trust this source? Is what they say going to be considered propitious and/or accurate?)

- Be skeptical. Verify patterns through sources. (i.e. don’t damage your #kairos opportunities through a lack of credibility).

Authdience, then, is a reminder that when we post on Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, Redditt, or whatever, we author a post, and get feedback from an audience who is an author. Even if we are just “Liking,” “Favoriting,” or “Downvoting” and “Upvoting” we are authdiencing—engaging in a process of authoring and audience-ing that is always

unfolding. Never being just one or the other, but always working as both. We like “authdience” because of how feedback allows us to make adjustments as authors and as audiences.

Episode 4: The Phantom Veils

Though Star Wars doesn’t have social media in the same sense we think of here in “real life,” we imagine that Jedi would suffer from FoMO. Described as “a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent, FoMO is characterized by the desire to stay continually connected with what others are doing” (Przybylski et al. 1841). It “refers to the blend of anxiety, inadequacy and irritation that can flare up while skimming social media like Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and Instagram” (Wortham). We imagine Luke, Anakin, and Yoda might have moments where they become distracted and stop “feeling” midichlorians as well as they should be. And Obi-Wan could have had a FoMO moment like this if he wasn’t “plugged in” to the Force: “How did I miss that great disturbance in the Force, as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced? I fear something terrible has happened and I missed it. I’m so out of it.”

FoMO “is hardly new. It has been induced throughout history by such triggers as newspaper society pages, party pictures and annual holiday letters—and e-mail—depicting people at their festive best” (Wortham). Social media and its connection to mobile technologies have seemed to make the fear more “Forceful” or omnipresent so that “as Ms. Fake [co-founder of Flickr] said, instead of receiving occasional polite updates, we get reminders around the clock, mainlined via the device of our choosing” (Wortham).

Though FoMO does have somewhat negative connotations, we see FoMO as an issue of #kairos—to be doing the right thing at the right time in the right place. To us, FoMO seems to be, at its core, a concern about kairos and being kairotic or the fear of missing kairos or acting akairotically. FoMO happens when an authdi or Jedi isn’t “plugged in”—isn’t veilling (surveilling, sousveilling, coveilling, and selfveilling), isn’t monitoring and responding to social media #kairotically. Veilling is a good way to begin thinking about and analyzing #kairos; veilling is a way to negotiate #kairos in/through social media. Veillances help us critique, recognize, and think about the needs of authdiences.

Because there is so much accessible information being produced in the digital realm, it becomes more important to know, in Rheingold's words, “who knows.” The “who’s who knower” or the person that knows knowers is a person who is relied on for kairos—

88

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

for knowing what (or who) might be valuable at a time and in a place. It’s really about knowing how to be propitious during a time and a place. So there’s a knack for knowing when to know when to know what, and where to know where to know what. Yoda, did we imitate just?

Though veils—surveillance in particular—often have negative connotations, we feel looking at rhetoric through this lens is helpful in utilizing, analyzing, and understanding #kairos. Such analysis really isn’t too different from what rhetoric and composition instructors already encourage and require students to do: audience analysis. So our purpose in this episode is to describe how using veils—of adding this rhetorical strategy in audience analysis—is useful for participating in a #kairos economy.

But we can’t really discuss #kairos, veillances, and social media without alsoconsidering algorithms. As many have noted (Pariser 2011, Andrews 2011, Deibert 2013, Schneir 2015, and Pasquale 2015) in their discussions of “big data” surveillance computer algorithms can adjust what we see or are given access to, and track our likes dislikes, searches, and online behaviors through cookies, deep packet inspection, and scraping, to name just a few surveillance tools. An audience member might only see content that supports his/her vision of the world: debate and argument might be foreclosed. Our browsing and searching and clicking behaviors might result in creepy advertising being posted on websites we visit; or it may result in weblining and price discrimination (Schneier). However, a lot of us don’t seem to mind the algorithm-troopers invading our web space. Rheti Schneier describes the tolerance users seem to have this way: “the bargain you make, again and again, with various companies is surveillance in exchange for free service [like Facebook, Twitter, or Google searching]” (4).

Behaving algorithmically, moreover, isn’t too far from what students are asked to do in rhetoric and composition classrooms. Whenever students use Burke’s Pentad or look at something through Aristotelian lenses, instructors are asking students to behave algorithmically: to follow “a step-by step process or set of operations to be followed to solve a particular problem” (Jones and Hafner 192).

“Big Data” technologies, unfortunately, are difficult to understand and to really know what’s going on—Pasquale and Deibert note how much they are like a “black box.” And in this way they are much like the Force. Deibert observes how big data technology is sort of “magical”:

The science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke argued that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” and as cyberspace grows more and more complex the more it becomes for most people a mysterious unknown that just ‘works,’ something we just take for granted.

Understanding just a little of this “magic,” or Force, can be useful—if not for using in their future communication practices then at least for understanding the ways veilling attempts to “solve” FoMO and practice #kairos effectively. Though, there are important problems with regards to privacy and ethics (weblining, the sale of your information, reputation damage through unfair algorithmic assumptions, and, of course, an overall “creepiness” to the whole thing), the information one can glean from veillances—from authdiance veillance—can be very helpful in a #kairos economy for negotiating these issues.

89

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

We’d like to introduce you to this sort of analysis, and we hope it inspires others to authdience these ideas—to respond, to develop them further, to get even more rhetorical with what we’re pitching.

In the four sections below, we’ll define the different veils, provide examples of each veillance, and describe the affordances and constraints of each5. What we offer is an algorithm for examining authdience through each lens. Individuals, authdi, or media producers shift between veilling positions depending on how they perceive themselves and their relation to others in terms of power and digital ethos6.

Surveillance

Surveillance or the veillance of an authority or power is:

Observation or recording by an entity in a position of power or authority over the subject of the veillance. (Mann, “Veillance and Reciprocal Transparency”)

Examples

- Jedis surveying the feelings of those who aren’t Jedi or don’t have Jedi powers (the Force).

- Teachers assessing student work (tests, essays, homework, etc.).

- Using an education platform’s—like Blackboard’s—metrics to see who’s accessing Blackboard and how: “Data includes the total overall time the student spent in the course as well as detailed information about the student's activity, such as which items and Content Areas the student accessed and the time spent on each" (from Blackboard's "Course Reports" help page).

- Companies, governments, individuals using website analytics (Google Analytics, Facebook’s Page analytics, Twitter analytics, Pew Internet Analytics, or demographic apps like Hootsuite’s Demographics Pro, Alexa) to sort and categorize visitors as types of consumers or citizens.

- Companies, governments, or individuals in a position of authority reading and evaluating web comments on a product, idea, blog, etc.

Affordances of Surveillance

- Allows authority to see what information is being viewed and responded to in terms of clicks, views, likes, people reached, and comments. Sorting and evaluating such information can be valuable in creating persuasive texts—i.e. style, delivery, arrangement, timing, and content—and includes collecting knowledge related to the metrics of what gets clicks and what gets read on the internet.

- Allows authority to profile and sort individuals and make kairotic predictions about behavior. Sorting and predicting can include original posts, but information such as who connects, likes, retweets, or otherwise participates in forms of viralization and information-sharing, can be surveilled as well.

- Enables authority to maintain reputation and remain an authority by allowing authorities to survey and respond to criticisms and/or misunderstandings.

Constraints of Surveillance

- Ethical considerations have to be acknowledged because surveillance allows authority to profile and sort individuals and make predictions about behavior, which can lead to stereotyping and, possibly, erroneous or dangerous assumptions about people. The data might not be accurate because one may not know the “black box” or the way the algorithm determines the demographic (e.g. will a person be marketed to as a “woman” because a person has searched for lipstick once as well as a pregnancy test? Or in an example Fertik and Thompson give in their prognostication about the importance of reputation: “Similarly, if a life insurance company wants to know what premium to offer you, it could easily assign you a health score based on the frequency of your doctor visits, the duration of your gym membership, the number of monthly credit card charges to the Cheesecake Factory, and any other factors its algorithms know to be connected to health and longevity”).

90

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

- The amount of data collected may make it difficult to tease out “knowledge” or meaning from noise.

- Allows authority to assess reputation of individuals. In hiring practices this can result in unfair assessments of ability and personality.

- May result in repetition where style, delivery, arrangement, timing, and content become mundane. The informed “clickbait” stops working because of tunnel vision guided by big data.

- What gets clicked or read isn’t necessarily quality content and may assume a more or less source-savvy audience. Actions based on surveillance, therefore, may contribute to the proliferation of lower quality, borrowed-without-attribution “clickbait” style content becoming the norm as Marantz observes.

Sousveillance

Sousveillance is the

Observation or recording by an entity not in a position of power or authority over the subject of the veillance. (Mann, “Veillance and Reciprocal Transparency”)7.

Examples

- Princess Leia sousveying the Deathstar in order to obtain information that will destroy it.

- Students assessing their instructors or school in evaluations.

- Curating authority figures and/or experts in Twitter lists, following, and learning from these experts or authority figures.

- Becoming friends with authority figures in a field and “Liking” or reviewing comments and commenting on Facebook profiles and pages.

- Commenting on a product, place, or service on Amazon, Yelp, or Angie’s List.

- Monitoring what the surveyors are collecting.

Affordances of Sousveillance

- Enables one to get a bead on authority and reputation of surveyors. By watching the watchers, one can get a sense of who knows who knows what.

- Enables for curation of experts and analysis of what’s successful to those in power (e.g. experts in the field) and determine what’s current and what’s relevant in a discussion.

- Provides opportunity for authdi to observe authority to ascertain holes, niches, angles, that haven’t been discovered so that he/she might develop an authority and reputation of his/her own and experiment with style, delivery, arrangement, timing, and content8. This creates a sort of surveillance-sousveillance feedback loop.

- Allows sousveyers to voice opinion, review, and possibly enhance reputation through contact with a surveyor.

Constraints of Sousveillance

- It may not be possible to know everything that’s been collected about oneself or how it’s being done and, for many people, it isn't possible to authdi algorithms that generate one's own metrics.

- Surveyors have power over sousveyors, and comments or critiques by souveyors may be ignored, deleted/silenced, or, in worst case scenarios, used to damage their reputations or ability to communicate (example: Facebook deleting accounts).

Coveillance

Coveillance is

“peer to peer” and occurs when ordinary citizens engage in [monitoring] practices on one another (Rainie and Wellman 39). Being a coveyor is important for observing what those around you are doing.

91

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

Examples

- Jedis feeling each others’ Forces (There's gotta be a better way to put this).

- Students or instructors providing feedback to each other informally. ***The formal transforms this into surveillance (where consequences of feedback is a metric for grades, raises, tenure etc.).

- Twitter backchannel conversations during a presentation by authdience members or those following the hashtag conversation.

- Reading and evaluating comments, favorites, likes, and ratings of products or peer posts by “regular” people on Amazon, Angie’s List, and Yelp.

- Watching Facebook Messenger and interpreting the meaning of the response time, knowing that the person you messaged has in fact seen your message.

- Watching the “Activity” section of a co-written Google Doc and assessing who is participating and how much and is it on time and determining if it’s “time” for you to participate more.

- In general, reading and evaluating what peers are saying.

Affordances of Coveillance

- Observe how peers are responding to authority in comments and ratings to make informed decisions. Monitoring what they are clicking, retweeting, sharing, and liking?

- Learn about peers’ research, politics, etc. and locate colleagues, partners, and other authdi for networking.

- From our experience, coveillance often results in what might be called “variety learning” where perspectives and information from alternative positions and surveyors can be discovered.

Constraints of Coveillance

- Peer comments may be limited or biased, especially if the sample is small. It may be difficult to find a more balanced perspective.

- Can limit perspective by enabling one to generate his/her own filter bubble or algorithm in which authdience is not seeing varied perspectives on issues.

Selfveillance

Selfveillance is a term coined by one of Paul’s new media writing students (Baumgardner). It refers to a meta-type of observation in which a person observes him/herself as an authdience.

Examples

- When Luke searches his feelings and evaluates himself and his connection to the Force.

- When instructors evaluate their evaluations.

- When individuals search back on Facebook timelines or Twitter feeds and evaluate their own posts and feedback they’ve received.

- Using a FitBit or Apple Watch or other such gizmo to monitor movement or heart-rate and making behavior adjustments based on the reading.

- Googling oneself and examining one’s digital footprint, reputation, and the news one is filtered. This might also be considered a form of sousveillance; however, because it is directed at oneself and not outward—where one might sousvey what Google collects in general—we’re putting it here. Selfveillance is specifically about monitoring one’s own online behavior and its interpretation.

Affordances of Selveillance

- Allows one to monitor and evaluate one’s own digital footprint and reputation.

- Allows one to make a sort of reputation plan—a plan that helps move the good information to the top of search engine hits and the less pertinent or “bad” information to the bottom by adding positive content and/or deleting negative content.

92

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

- Content is remembered. There is a growing history of one’s successes and failures at communication.

Constraints of Selfveillance

- It is difficult and in some cases it may be impossible to delete slander or “bad” information since data miners (including popular social media platforms like Facebook) may never completely delete a post or a browser trail you’ve been on.

- As mentioned in “affordances,” content is remembered. There is a growing history of one’s successes and failures at communication.

- Because of how content may be remembered and changed, selfveillance might gaslight your own memory where you remember more synecdochally (more parts for whole or whole for parts). Go to “Like Me, Like Me Not” and click on the read petal for more about gasligting and the web9.

As we can see through the above examples, veillances are central to establishing credibility, exercising power, and negoatiating right time and place in a #kairos economy. The place of veillances in a #kairos economcy is also reflected in Rheti Rheingold’s discussion of networks and net smarts:

In previous eras, it may have been true that ‘it’s not what you know but who you know.’ Today, how you know who you know matters as much as who you know, and one of the most valuable traits a person could have in a twenty-first-century organization is a knack for knowing ‘who knows who knows what.’ (24)

In more words, because there is so much accessible information being produced in the digital realm, it becomes more important to know “who knows.” The “who’s who knower” or the person that knows knowers is in a sense a person who is relied on for kairos—for knowing what (or who) might be valuable at a time and in a place. So for us, as we said before, it’s really “who knows who knows what, where, and when.” It’s really about knowing how to be propitious during a time and a place. So there’s a knack for knowing when to know when to know what, and where to know where to know what. Yoda, did we imitate just? Using veillances is a lens for sorting the “who’s who knowers” in a #kairos economy. We hope our introduction to this sort of analysis inspires others to continue developing these ideas for increased rhetorical awareness and rhetorical practice.

The #Kairos Awakens

Rhetoric is a Jedi mind trick. Like Obi-Wan Kenobi, the orator sets out to make you see things his way (Kindle location 56–57).

Sarah Spence

In the introduction to her book exploring how to apply rhetoric and figurative language to contemporary situations, Sarah Spence’s parallel is attention getting. Admittedly, the material wasn't extremely kairotic when it was published (Episode III came out in 2005 and The Clone Wars didn’t come out until 2008); however, Star Wars content is evergreen. Its timeliness ebbs and flows along a somewhat consistent path.

In a number of ways we agree with Spence. We like seeing ourselves as Jedis and think there is some value in seeing rhetoric as a “Force.” There is value in showing parallels between rhetoric, #kairos, our current technological and/or social media moment, and the Force. Spence continues her parallel and writes that “Unlike Jedi,

we cannot persuade simply by accompanying our words with a wave of the hand.

93

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

Other methods have been found to accomplish the same goal, which involve the rhetorical use of language.” Here, however, we disagree. The wave of a hand by an authority is quite rhetorical and can be quite persuasive and seem Forceful. Though Spence is certainly commenting on the less rhetorical aspects of being a Jedi, like telekinesis, telepathy, and clairvoyance, we feel such Jedi moves are rhetorical. The Jedi are selecting from their rhetori-Forceful toolkit to accomplish tasks kairotically.

Social media is beginning to look very similar to the Force in how it’s being deployed and how metrics are used. In a lot of ways this has become “magic” like the Force because we don’t really understand how it works, or consider how to use it, or consider it #kairotically. Though there are issues with privacy and cyber crime, we’d definitely rather deal with social media metrics than Force metrics. This may come as a shock if you’ve been with us all along, but for us, the Force is really part of a dark side.

Users of the Force are part of an elite and exclusive club: The Jedi club. You either have Force or you don’t. Unlike with a #kairos economy, you can’t really join the club through researching, practicing, becoming an authdience, becoming a curator, and knowing who knows who knows what. It’s difficult for outsiders to know propitious times and places to Jedi. The Force isn’t, furthermore, accessible. Accessibility is vital to surviving in a #kairos economy.

The Jedi only use one search engine, one data collector, one algorithm, and/or one social media platform—the Force. The Force seems to be pretty biased. How can one #kairos when the possibilities of surveillance, sousveillance, coveillance, and even selfveillance are limited to a single “technology”? So the Force is an ultimate filter bubble and/or walled garden.

Finally, we aren’t complete techno-determinists. We value Han Solo’s point:

Kid [Luke Skywalker], I've flown from one side of this galaxy to the other. I've seen a lot of strange stuff, but I've never seen anything to make me believe there's one all-powerful Force controlling everything. There's no mystical energy field that controls my destiny.

We believe in authdiencing and the power of being a rhetor operating within constraints—be they the constraints of the Force, the media platform, or the veil. While

such constraints can guide communication, and metrics like analytics can give one better odds at effective communication, an authdi has agency as an author and an audience to transform texts and make decisions about how to use information.

So here’s a summary of our authdience point of view.

It's important to think of ourselves as being in a #karios economy. With all the information out there, rhetors need to be aware of when and where to be timely and placely to get their message out. #karios is a way to think about Rheti Jenkins’ aphorism about media: If it doesn't spread, it's dead. And to spread and live is to pay attention to #kairos, displaying a what at an important when and where.

Examining veillances in a variety of forms can be good tools and lenses for living in an economy based on #kairos and considering the ethical dimensions of using these tools—i.e. how they work with other economies like the emerging attention (Lanham) and

reputation economies (Fertik and Thompson). Such analysis helps us use, see, and

examine the Force that is social media.

So we want to leave you with a final bit of authdi wisdom:

94

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

Keep your smartphones by your side because these are the weapons of ominpresence and omniplaceness; these are the weapons of the Authdi knight.

May the #kairos be with you!

Notes

- For more information about the rhetoric of awkward, see Muhlhauser and Kachur's vlog (“Episode 2: Aporia”) on aporia and using it effectively.

- The examples of invented and situated kairos come from Muhlhauser and Schafer's analysis of gender, materiality, and rhetoric in “Daily Gas: Rhetoric, Bodies and Beano.”

- Additionally, we feel that sometimes nuance isn’t needed or isn’t really being looked for by audience members. Sometimes just being aware of how something works, knowing a little about the language or concept, helps an audience member get by in certain places and times. Sometimes having a way to get into a literacy or discourse is good “cocktail party” knowledge.

- Sharing and distributing was implied and not explicit in Scoble's discussion of curation.

- For us affordances are “feature[s] of a cultural tool [or tools] which makes it easier for us to accomplish certain kinds of actions” (Jones & Hafner 192). Constraints are “feature[s] of a cultural tool [or tools] which makes it more difficult to accomplish certain kinds of actions” (Jones & Hafner 193).

- Mann offers different definitions and interpretations of surveillance and sousveillance in his analyses of the concepts. We chose his hierarchical examples because they lend themselves to the kind of author and audience relationship we describe in this work.

- For us, digital ethos is what Rheingold describes in his paraphrase of “The Elements of Computer Credibility" by Fogg and Tseng. They “stress that credibility is always a perceived quality, and not a property that can be found in any human or computer product.” For better or worse, digital metrics attempt to turn this conception into something more perceptual, more concrete.

- We're not sure where this falls with regards to surveillance and sousveillance but there is an exciting and new sort of viewing occurring: crowdviewing. The term—coined by the creator of kosmos (mentioned by one of the actors, Terry Malloy)—is an experimental distribution method in which the audience is asked to share (through social media), the online science fiction series. To unlock the each of the five films, the audince has to meet a certain number of views. Distribution and advertising become reliant on audience participation.

- The article “Like Me, Like Me Not” (Muhlhauser and Campbell) discusses gaslighting and the web in a little more depth. Click on the red petal to locate the discussion.

Works Cited

“Accessibility.” W3C. W3C. 2015. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

Andrews, Lori B. I Know Who You Are And I Saw What You Did : Social Networks And The Death Of Privacy. New York: Free Press, 2012. Kindle file.

95

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

Baumgardner, Amy. “Selfveillance.” Class discussion. Fall 2013.

Chandler, Daniel. “Paradigms and Syntagms.” Semiotics for Beginners. 3 July 2014. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

“Course Reports.” Blackboard. Blackboard. n.d. Web. 27 Sept. 2015.

Deibert, Ronald. Black Code: Inside The Battle For Cyberspace. Toronto: Signal, 2013. Kindle file.

Fertik, Michael, and David Thompson. The Reputation Economy: How To Optimise Your Digital Footprint In A World Where Your Reputation Is Your Most Valuable Asset. New York: Crown Business, 2015. Kindle file.

Ferguson, Kirby. “Everything is a Remix: Remastered.” Online video clip. Vimeo. Vimeo, updated Sept. 2015. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

Fogg, B. J., and Hsiang Tseng. “The Elements of Computer Credibility.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: The CHI Is the Limit. Pittsburgh: ACM Press, 1999. Print.

Bizzell, Patricia. “The Intellectual Work of ‘Mixed’ Forms of Academic Discourse...” ALT DIS: Alternative Discourses And The Academy. Eds. Christopher Schroeder, Helen Fox, and Patricia Bizzell. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook; Heinemann. 1-10. 2002.

Harker, Michael. “The Ethics of Argument: Rereading Kairos and Making Sense in a Timely Fashion.” College Composition and Communication 2007: 77. JSTOR Journals. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

“Introduction to Web Accessibility.” W3C. W3C. February 2005. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

Iskold, Alex. “The Attention Economy: An Overview.” readwrite. 1 March 2007. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

Jenkins, Henry. Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. New York : Routledge, 2013. Kindle file.

Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York U. Press, 2013. Kindle file.

Jones, Rodney H., and Christoph Hafner. Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Kinneavy, James L. “Kairos in Classical and Modern Rhetorical Theory.” Rhetoric And Kairos: Essays In History, Theory, And Praxis. Eds. Phillip Sipiora and James S. Baumlin. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002. 58-76. Print.

---. “Kairos: A Neglected Concept in Classical Rhetoric.” Rhetoric and Praxis: The Contribution of Classical Rhetoric to Practical Conditioning. Ed. Jean Dietz Moss. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1986. Print.

96

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

Lanham, Richard A. The Economics Of Attention: Style And Substance In The Age Of Information. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006. Print.

Lynch, Patrick J., and Sarah Horton. Web Style Guide. 3rd ed. Web. 20 Aug. 2015.

Mann, Steve. “Veilance And Reciprocal Transparency: Surveillance Versus Sousveillance, AR Glass, Lifeglogging, And Wearable Computing.” Wearcam. Web PDF. 12 Sept. 2015.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001. Print.

Marantz, Andrew. “The Virologist.” The New Yorker. 5 Jan. 2015. Academic OneFile. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

Miles, Libby. “Rhetorical Work: Social Materiality, Kairos, and Changing the Terms.” Journal of Advanced Composition. 2007: 27. JSTOR Journals. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

Molloy, Terry. “Kosmos - The Web-Series: from Kickstarter to Kompletion!” Intervention 6. Hilton Hotel, Washington DC/Rockville, MD. 15 August 2015. Presentation.

Muhlhauser, Paul and Andrea Campbell. “Like Me, Like Me Not.” H arlot: A Revealing Look at the Arts of Persuasion. 8 (2012). Web.

Muhlhauser, Paul and Robert Kachur. “Episode 2: Aporia.” Online video clip. Vimeo. Vimeo, Aug. 14 2014. Web.

Muhlhauser, Paul and Daniel Schafer. “The Daily Gas: Rhetoric, Bodies, and Beano.” Women and Language. W&L Online, Nov. (2015). Web.

Pariser, Eli. “Beware Online ‘Filter Bubbles.’” Online video clip. TED. TED, March 2011. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

Pasquale, Frank. The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money And Information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015. Kindle file.

“Produsage.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 26 August 2015. Web. 27 Sept. 2015.

“Prosumer.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 6 Nov. 2015. Web. 24 Nov. 2015.

Przybylski, Andrew K., et al. “Motivational, Emotional, And Behavioral Correlates Of Fear Of Missing Out.” Computers In Human Behavior 29.(2013): 1841-1848. ScienceDirect. Web. 27 Sept. 2015.

Rainie, Harrison, and Barry Wellman. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2012. Kindle file.

Rheingold, Howard. Net Smart: How To Thrive Online. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012. Kindle file.

97

THE FORCCCE A LONG:TIME AGO / IN A GALAXY FAR, FAR AWAY...

Ridolfo, Jim, and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss. “Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery.” Kairos 13.2 (2009). Web. 25 Aug. 2015.

Rivers, Nathaniel A. “Episode Seven: Kairos.” Online video clip. Enculturation. Web. 13 Sept. 2015.

Schneier, Bruce. Data And Goliath: The Hidden Battles To Collect Your Data And Control Your World. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015. Kindle file.

Scoble, Robert. “Robert Scoble on Online Curation.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 7 March 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2015.

Spence, Sarah. Figuratively Speaking: Rhetoric And Culture From Quintilian To The Twin Towers. London : Duckworth, 2007. Kindle file.

Spooner, Michael. “An Essay We’re Learning to Read.” ALT DIS: Alternative Discourses And The Academy. Eds. Christopher Schroeder, Helen Fox, and Patricia Bizzell. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook; Heinemann. 139-154. 2002.

Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace. Dir. Geore Lucas. Perf. Liam Neeson, Ewan McGregor, Natalie Portman, Jake Lloyd, Ian McDiarmid. 20th Century Fox, 2001. DVD.

Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones. Dir. Geore Lucas. Perf. Ewan McGregor, Natalie Portman, Hayden Christensen, Ian McDiarmid, Samuel L. Jackson, and Christopher Lee. 20th Century Fox, 2002. DVD.

Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith. Dir. Geore Lucas. Perf. Ewan McGregor, Natalie Portman, Hayden Christensen, Ian McDiarmid, Samuel L. Jackson, and Christopher Lee. 20th Century Fox, 2005. DVD.

Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. Dir. Geore Lucas. Perf. Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Peter Cushing, and Alec Guinness. 20th Century Fox, 2006. DVD.

Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back. Dir. Irvin Kershner. Perf. Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Billy Dee Williams, and Anthony Daniels. 20th Century Fox, 2006. DVD.

Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi. Dir. Richard Marquand. Perf. Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Billy Dee Williams, and Anthony Daniels. 20th Century Fox, 2006. DVD.

Thompson, Roger. “Kairos Revisited: An Interview with James Kinneavy.” Rhetoric Review 19 (2000): 73-88.

Warnick, Barbara, and David S. Heineman. Rhetoric Online: The Politics Of New Media. New York: Lang, 2012. Print.

98

MUHLHAUSER, BLOUKE, AND SCHAFER / MAY THE #KAIROS BE WITH YOU

WebAIM. Web Accessibility In Mind. Utah State University. Web. 27 Sept. 2015.

Wortham, Jenna. “Feel Like a Wallflower? Maybe It’s Your Facebook Wall.” New York Times 9 April 2011. Web. 1 Sept. 2015.

Yergeau, Melanie, Elizabeth Brewer, Stephanie Kerschbaum, Sushil K. Oswal, Margaret Price, Cynthia L. Selfe, Michael J. Salvo, and Franny Howes. “Multimodality in Motion: Disability and Kairotic Spaces.” Kairos 18.2 (2013). Web. 1 Dec. 2015.

Paul Muhlhauser

Paul Muhlhauser is an assistant professor of English at McDaniel College in Westminster, Maryland. His work has appeared in Harlot: A Revealing Look at the Arts of Persuasion, Women and Language, and Computers and Composition Online. He makes beautiful websites, loves his chickens, and is a gentleman farmer.

Cate Blouke

Cate Blouke is an Assistant Professor of English and Director of Digital Pedagogy at Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Her work has appeared in Harlot: A Revealing Look at the Arts of Persuasion, Comedy Studies, and Arts & Culture Texas. She loves her dog, takes pride and solace in her baking, and writes letters by hand even though she teaches about the digital.

Daniel Schafer

Daniel Schafer is visiting assistant professor in the Department of English at McDaniel College in Westminster, Maryland. His work has appeared in Harlot: A Revealing Look at the Arts of Persuasion, Women and Language, and Journal of Global Health. He loves hot tea, evergreen trees, and running mountain trails of the Pacific Northwest with his wife, Katie.

99