Carolyn Handa (2001) aptly noted that "preparing students to communicate in the digital world using a full range of rhetorical skills will enable them to analyze and critique both the technological tools and the multimodal texts produced with those tools." The world for which we are preparing students to communicate as thinkers, researchers, professionals, and citizens has changed in recent years. For instance, up until fairly recently, the fairly expensive and incredibly powerful graphic-design application Adobe Photoshop was only available to a small group of highly trained designers. Now "Photoshop" has become a verb, and many college campuses make it accessible on their computer networks. Further, shareware applications like Gimp and online image-manipulation tools that create a Photoshop-like environment (e.g., Pixlr and Splashup) are readily available.

Not only are the tools more readily available, but the spaces to distribute graphic work are more easily accessible. Returning again to a world in which Photoshop was primarily used by high-end designers, graphics had to be printed to be shared, and full-color, high-resolution printing was incredibly expensive and it was often time-intensive to prepare images for print production. Today, there are abundant digital spaces on which and through which composers can post and share graphic work, including social-networking sites.

Cindy Selfe (2004) defined visual literacy as necessitating a relationship between both consumption and production: "the ability to read, understand, value, and learn from visual materials (still photographs, videos, films, animations, still images, pictures, drawings, graphics)--especially as these are combined to create a text--as well as the ability to create, combine, and use visual elements (e.g., colors, forms, lines, images) and messages for the purposes of communicating.... visual literacy (or literacies), like all literacies, are both historically and culturally situated, constructed, and valued."

Other scholars in rhetoric and composition have emphasized the importance of both looking at and making different types of texts (George, 2002; Hocks, 2003; Shipka, 2005, 2011; Yancey, 2004), and, certainly, producers of multimodal work recognize the ways in which analysis and production inform each other. In this article, we attend more to the analytical practices, because although rhetoric and composition has a long, rich history of deeply interrogating texts (both alphanumeric and image-based), we haven't particularly honed in on the ways in which digital tools allow for the easy manipulation of images, or attended to the ethical implications of such manipulation.

Historically speaking, image manipulation is certainly nothing new. However, the accessibility of graphic-design tools and the spaces and places for distributing images are relatively new. Further, the tools and the spaces place significant expectations upon us as viewers/readers and producers/creators. Culturally speaking, although we generally know better, our culture tends to cling to a sense of photographic truth and machine objectivity. New technologies allow us to represent ourselves--and, more importantly--to represent others in ways that are potentially problematic. Indeed, we currently live in a culture of simulation--where images are created, or where arguments are created through photographic manipulation.

Rhetorical ethics, a framework and lens offered by Jim Porter (1998) for navigating online and internetworked dynamics generally lends itself well to negotiating digital-visual considerations. What makes an ethical approach specifically "rhetorical?" According to Porter (1998), "'Being rhetorical' means attending to situated contextual features that form, maintain, and constrain discursive relations... and acknowledging the role of technologies, institutions, disciplines, and other modes of system and production in constituting and constraining human relations" (p. 146). Rhetorical ethics situates "questions about human relations as they are constructed and maintained through discourse" (Porter, 1998, p. 146). Certainly, in a networked, digital world, images are part of the rhetorical landscape, and part of our discursive processes.

Porter (1998) defines rhetorical ethics against a universal, one-size-fits-all approach to analysis: "Rhetorical ethics is procedural, it is case specific, it provides some principles (although it does not trust them very much, as it is sensitive to the mandates of particular situations), and it privileges the specific and the concrete over the general and abstract. For these reasons, and because of its flexibility and adaptability in the face of tough cases, it offers an extremely powerful paradigmatic perspective" (p. xiii).

Porter emphasizes the collective nature of rhetorical acts, and the ways in which we act in "bound and localized" ways. Porter asks questions of rhetorical action, addressing the presence of ideological and power dynamics, but also asks questions of practical judgment: "How do we arrive at a standpoint, recognizing that any act of writing requires taking one? How do we decide what to do, what action to take in situations involving competing ideologies?" (p. 31). For the purposes of this article, here we expand the ways in which "writing" is situated, combining the multimodal work of computers and writing scholars with the rhetorical ethics framework offered by Porter. Writing, today, requires composers to draw across multiple modes of meaning making. Rhetorical positioning--that is, finding a standpoint from which to analyze and to act, to critique and to compose--requires attention to the ways in which both words and images are used to express, inform, persuade, etc.

Porter (1998) points out that "rhetorical acts presume both and obligation and a judgment, which are part of, not prior to, the rhetorical act" (p. 53). Thus, rhetorical ethics are those principles that account for and accept "the presence of ideology, power, and politics" but that also "address the problem of practical judgment" (p. 31). How does one do what Porter calls for? How does one sufficiently attend to the issue of "practical judgment" in specific instances of critical digital-visual analysis? We use Porter's approach to frame the questions--and how we ask those questions--when engaging in critical visual analysis.

Specifically, we ask:

- What is the context--social, cultural, historical--for the visual analysis?

- How is the visual analysis situated according to local ethical practices and conventions? That is, how is this instance situated according to the ethical practices of cultures, communities, institutions, etc.?

- What is at stake for us in considering this visual? How are we positioned in relationship to the visual? What kind of producers/consumers are we?

- What is at stake for others in regard to this visual? How are others positioned in relationship to the visual? How do we understand their roles as producers/consumers?

- What are the specific technological/material conditions of the visual, and how do we attend to these conditions in making ethical judgments?

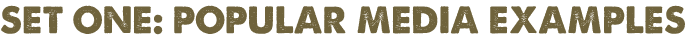

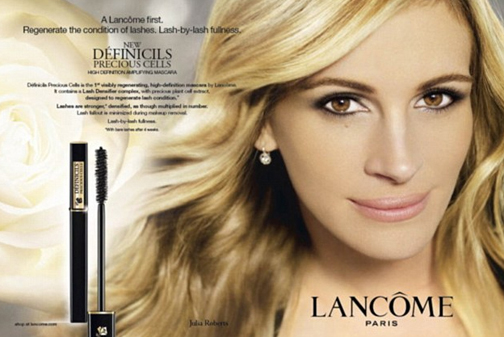

We present below four sets of visuals ripe for critical analysis. We introduce and briefly discuss each set of images, and pay particular attention to one image from each set. After discussing each set of images, we return to the questions we've crafted drawing from Porter's (1998) work and present some pedagogical and research-related implications and conclusions.