Like project two, the

third project is also structured around the notion of interconnectivity;

project three, however, focuses on evoking what Giorgio Agamben calls

"whatever singularities." For this project, I assign smaller

tasks so that students are not overwhelmed. As in project two, I present

the students with a problem:

Problem: In The

Coming Community, Giorgio Agamben discusses the possibility

of a new planetary humanity. His solution is the Whatever, or quodlibet.

Although one could never foretell precisely the coming of events--how

many of us could have predicted the destruction of the World Trade

Center on September 11?--one might say that we as a society could

effect a change. Agamben, along with other hopeful citizens, see

the Whatever as the beginning of hope. Our section of ENG 1131 will

attempt to "test" Agamben's theory. The question we are

trying to answer is, "Does the Whatever provide happiness or

an ineffable experience for us?"

I

then assign four exercises, which will lend themselves to the final

project. In the first exercise, students are required to write, in

300-600 words, about Roland Barthes' Camera Lucida. They must

explain what Barthes draws from photography and what people might

possibly see or experience in a photograph. Then, students must explain

in about 10 to 12 sentences what Barthes means by punctum,

which refers to an element in a photograph that pricks or wounds a

viewer. Punctum is not something that generally interests someone,

such as a beautiful sunset or, most currently, a collapsing building,

which might invoke a recollection of 9-11, thus a national identity.

In locating punctum, Barthes wishes to locate only what he

himself could see, not what others saw. Punctum was his way

of forging an individuality; it occurs when one least expects it.

It is a small, overlooked detail--here is where "Observing the

Ordinary" returns to the course--in a photograph that evokes

or triggers a memory, that enables the viewer to appropriate the photograph

for herself. The 10 to 12 sentences serve a guide for the photographs

that the students must choose for exercise two.

I

then assign four exercises, which will lend themselves to the final

project. In the first exercise, students are required to write, in

300-600 words, about Roland Barthes' Camera Lucida. They must

explain what Barthes draws from photography and what people might

possibly see or experience in a photograph. Then, students must explain

in about 10 to 12 sentences what Barthes means by punctum,

which refers to an element in a photograph that pricks or wounds a

viewer. Punctum is not something that generally interests someone,

such as a beautiful sunset or, most currently, a collapsing building,

which might invoke a recollection of 9-11, thus a national identity.

In locating punctum, Barthes wishes to locate only what he

himself could see, not what others saw. Punctum was his way

of forging an individuality; it occurs when one least expects it.

It is a small, overlooked detail--here is where "Observing the

Ordinary" returns to the course--in a photograph that evokes

or triggers a memory, that enables the viewer to appropriate the photograph

for herself. The 10 to 12 sentences serve a guide for the photographs

that the students must choose for exercise two.

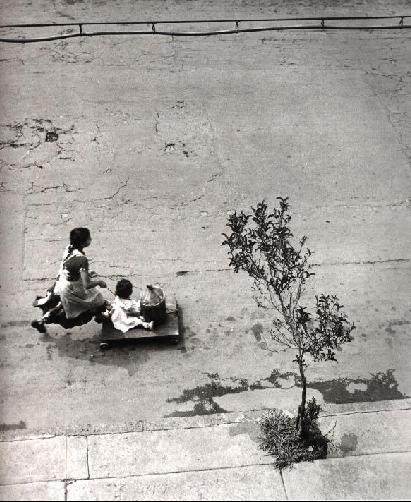

In exercise two, students

must find three photographs in which they identify punctum. They may

not use photographs with which they are already familiar or any that

they have taken as a photographer. The photos must also be black and

white and have been taken before their birthdates. Then, in about

300 words or less--no less than 50 words each, though--students must

articulate what punctum in each photograph might be for them.

That is, they must identify the detail in a photograph that triggers

a memory, and they must describe the memory. (Notice another theme--memory--that

returns to us later in the semester.)

For

exercise three, students must generate haikus for the three photographs.

I incorporate haikus largely because Barthes likens the haiku to the

photograph. The haiku also forces students to pay closer attention

to detail and language, again, two themes that we explored earlier

in the semester in "Observing the Ordinary" and semiotics,

respectively.

For

exercise three, students must generate haikus for the three photographs.

I incorporate haikus largely because Barthes likens the haiku to the

photograph. The haiku also forces students to pay closer attention

to detail and language, again, two themes that we explored earlier

in the semester in "Observing the Ordinary" and semiotics,

respectively.

Last, for exercise four,

students must select a film of which they are fond, but do not really

know or have never figured out why. The task then is for the students

to view the film as they would a photograph, to recall specific scenes

as one would locate specific details. Essentially, students want to

describe their relationship with the film in terms of punctum.

For the final project, once

the students have completed the four exercises, they begin to create

a Whatever space by making connections with their assignments. There

are three parts to the evocation of project three. The requirements

for first two parts are as follows: 1) Students must scan or download

two or three images of themselves for the project. How they incorporate

the images is at their discretion; 2) Students must recall the experience

of watching the film that "pricked" or "wounded"

them and chronicle that experience in about seven or eight sentences.

They must then articulate this experience using scenes or images from

the film and should be able to complete the second part in about seven

web pages.

After completing parts one

and two, students must incorporate the three photographs, the punctum

explanations, and the haikus. The result should be to evoke an experience,

a whateverness. In this Whatever space, they make connections not

based on logic but on a feeling, an emotion, however the student sees

fit. So, no connection is ever wrong.

The

third project is the third approach to one's identity, drawing primarily

from experiences and emotions. If the first project serves as an initial

examination of who the student believes s/he is, and the second project

accounts for how family and society contribute the construction of

the student, the third project attempts to explore one's identity

outside of social and political forces. The third project encourages

the student to look inward, to try escaping those binaries or stereotypes

that they are forced to bear as citizens. The project demands that

the student not identify with a certain group or nationality, but

exist herself or himself. So, if I could reformulate the relationship

between the student and projects, I would suggest that the student

in project one only "thinks" s/he is different, the student

in project two realizes that s/he may be similar to many people after

all, and the student in project three believes that there is a hopeful

possibility that s/he may in fact be an individual, a singularity.

The

third project is the third approach to one's identity, drawing primarily

from experiences and emotions. If the first project serves as an initial

examination of who the student believes s/he is, and the second project

accounts for how family and society contribute the construction of

the student, the third project attempts to explore one's identity

outside of social and political forces. The third project encourages

the student to look inward, to try escaping those binaries or stereotypes

that they are forced to bear as citizens. The project demands that

the student not identify with a certain group or nationality, but

exist herself or himself. So, if I could reformulate the relationship

between the student and projects, I would suggest that the student

in project one only "thinks" s/he is different, the student

in project two realizes that s/he may be similar to many people after

all, and the student in project three believes that there is a hopeful

possibility that s/he may in fact be an individual, a singularity.